.........Wednesday night I was fortunate enough to have a wonderfully clear night, so I was able to double-check all of my impressions of the appearances, the methods of finding Messier Objects, and the maps that I have made for this purpose. Each of the Messier objects will appear with a star map showing you how to get from a bright (well, fairly bright ... well, identifiable) star to the object. Each map will be on a different scale -- some objects are close to bright stars, and some require more of a trip. On each map will be indicators matched to the field of view of common telescopes. If you can fit the entire full moon in the field of view of your telescope, then you can use my circles as good guides as to the sizes of the steps that you are going to have to make to get where you need to go.

..........Because of the name of the blog, my first pass through the sky (the first year of the blog) will cover the Messier objects, constellation by constellation. (For most constellations, I’ll be able to do this in the same entry; the Big Dipper is unusual.) There are seven (eight) Messier objects in the area of the Big Dipper, and I’ll cover them in numerical order. This is a bit unfortunate, because the first Messier object on the list, the first Messier object I’ll cover here, is …

M 40: The Lamest Messier Object of Them All …

Difficulty Level: 2 (Close to a bright star, only one jump.)

.........Because M40 is the lowest-numbered Messier object in the first constellation I’m talking about then this is the first one I’m covering, which is a bit unfortunate, all things considered. Responding to the report of Johann Hevelius, who claimed to see a nebulous patch in this area, Charles Messier attempted to find the object at the location the other astronomer gave, only to discover nothing at all. It’s quite possible that the original observer actually did see a comet but didn’t recognize it as such, and recorded it essentially as "gunk that gets in the way of identifying comets".

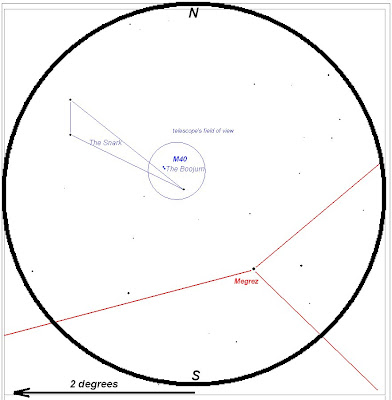

..........For some reason, Messier felt the need to identify something in the area with Hevelius’s observation, so a double star was identified as “M40”. (As it turns out, this even isn’t a double star, but simply two stars along the same line of sight.) If you would like to find this “object”, the path is easy enough. Start with d Ursa Majoris (Megrez), the star connecting the handle to the bowl. Just above Megrez is a triangle of stars that should all appear easily enough in your finder scope or binoculars, which leads me into a bit of an aside, since this is the first example of star-hopping that I'm using.

........When mapping a way from a bright star to a fainter object of interest, I’ll use patterns of stars (asterisms) to help fix the image in memory, but in this case I was a bit put off because it is a little hard to make anything besides a triangle from three nonlinear stars, but inspiration has struck, and I will name this asterism “the Snark”! (I'll explain this in just a second.)

.........To find M40, which I will therefore name “Boojum”, find the lowest star in the triangle (the one closest to Megrez) in the eyepiece, and the optical double which has inherited the name M40 will enter your field from the north if the star (which has the name 70 Ursae Majoris, unless you have a better name for it) is moved to the southern edge of your field. The Boojum is one of the easiest Messier Objects to find, and (sadly) one of the least interesting. Okay, it is the least interesting Messier Object.

.........Why does the substitute for a disappearing Messier object get named “the Boojum”? I took this from Lewis Carroll’s poem, “The Hunting of the Snark”.

.........To help you get an idea of the brightnesses of starts seen through the telescope, the two stars that are The Boojum are ninth magnitude (9.0), about the limit of stars in the smallest telescopes. It will be good to use this to get an idea of how easy it will be to find other Messier objects, ones that are a lot more interesting.

M 81 and M 82: "I'm not touching you, am I bugging you?" Galaxies

Difficulty Class: 3 (Some jumps through asterisms)

.........To my mind, the jewels of the Big Dipper are the two nearby galaxies (near to each other, and relatively close to the Milky Way) M 81 and M82. From my point of view, these are some of the easiest galaxies to find, although you may find differently. These were some of the first deep-sky objects that I learned to find, so the asterisms that I use to find them might not appear to be as obvious to you.

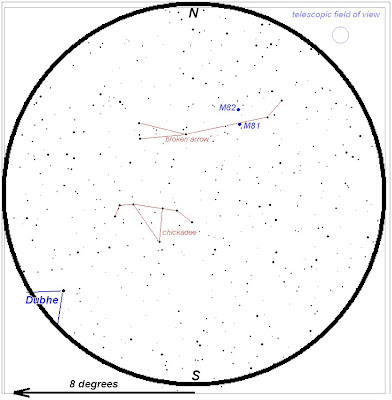

Start at the end of the Dipper bowl (the star Dubhe), look north of Dubhe, and a bit to the west. In less of a shift than it would take to go from Dubhe to Merak, you will find some stars that appear to me to be a mirror-reversed Greek letter tau. Since I’m printing this on a map instead of just trying to remember a path at the telescope, I am naming this the asterism "The Chickadee". Once you’ve found this, center the Chickadee in the center of your binoculars/finder scope. If you now go due north, you’ll find what I call the broken arrow (this one needs a better name – any ideas?) : a triangle of stars that appears to me to be the back end of the arrow, which can be traced east to a star with another star of about the same brightness off the line, giving to me the appearance of a broken arrow. Visible in binoculars or a telescope’s finder scope as two faint fuzzy patches about two-thirds of the way closer to the break in the arrow than the fletching are the two galaxies we are looking for. (If you can’t see the galaxies in a finder scope, just aim for a point along the line of the arrow and hope for the best. (As always, if you don’t see the galaxies in the telescope then unlock the telescope and search in increasing circles from your starting point. Never underestimate the importance of patience in astronomy.)

..........M81 and M82 are reasonably close (as galaxies go) at a mere twelve million light years away. These galaxies appear close together in the sky because, in this case, they actual are close to each other – and they used to be closer, which affected in ways even visible now.

M81: Bode’s Galaxy

.........M81 was first discovered by Johann Elert Bode in 1774, and is often called "Bode's Galaxy". The total brightness of this galaxy is magnitude 6.9, implying that the object should be fairly bright, but this can be misleading. By luck, I started this so that the final constellations that I talk about will be constellations with a lot of galaxies. This is lucky because galaxies can be some of the hardest objects to observe. In stars, including clusters of stars, we’re looking at a lot of point sources of light – even with streetlights, moonlight, etc., clusters can still be seen. In galaxies and nebulae, the light is smeared over an area; any increase in the background light can drown out the image entirely.

..........Bode’s Galaxy is a fairly reliable target, a face-on spiral galaxy will two bright arms. It will appear as a bright smeared dot of light, and on the very clearest and darkest of nights, the two spiral arms of M81 will be visible as well.

.........I have an anecdote about Bode's Galaxy that I now feel compelled to share (otherwise, you ould just skip to the next paragraph.) In 1993, a supernova was observed in M81 and, as these things do, for a few weeks that one dying star gave out as much light as the rest of that galaxy. This made a lot of news, as there is lot of physics and astronomy that we can learn from supernovae, plus it was cool to watch. At that time, I was living close to Cape Canaveral, and had the opportunity to watch a night launch of the space shuttle. I had brought my telescope to the launch site to get a close view of the shuttle, but after a while of counting heat tiles, I began to get distracted. On a whim, and not expecting very much because we were surrounded on all sides by brilliant streetlights, I aimed the telescope at Dubhe, and moved the scope about as far as I remembered it being to the west, and then north, to get to M81, and looked in the telescope. By some astounding quirk of luck (although I tried to pretend that it was skill), I could see the field with M81 in the telescope! The galaxy was invisible due to all of the background light, but the star field plus the supernova was recognizable. There, my secret is now out.

M82: The Starburst Galaxy / Cigar Galaxy

.........With M81 in the center of the field of view, one can move the telescope so that M81 moves to out of the southern edge of the field of view, and then move the telescope gently along the other axis, and M82 will appear, a thin jagged line of light. The Starburst Galaxy is an irregular galaxy that can almost fit in the same field of view with M81. Galaxies are divided into four major groups: spiral galaxies, barred spiral galaxies (a spiral galaxy with a bar structure in the core), elliptical galaxies, and “irregular” galaxies, galaxies in which something has happened to distort the shape of the galaxy. In the case of M82, this was a close pass, in which M81 caused a lot of the gas clouds in M82 to collapse into new stars. More recent studies show that M82 is probably a barred spiral galaxy seen edge on, with the burst of new star formation somewhat hiding the shape.

M 97: The Owl Nebula m = 11.20

Difficulty Level: 5 (close to a bright star, but individually quite faint.)

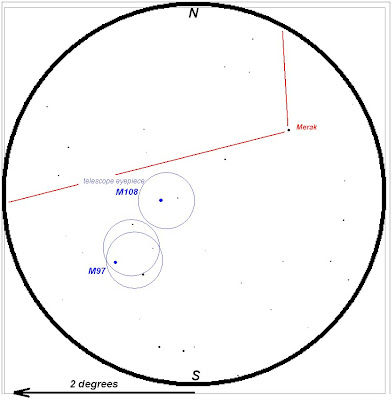

.........I’ve found the Owl Nebula one of the hardest Messier objects to find in the sky. At a total visual magnitude of 11.20, and that is considering all of the light concentrated at one point, which it most certainly does not. I wouldn’t advise looking for the Owl Nebula on anything but clear, moonless nights.

.........The Owl Nebula is a planetary nebula, made up of a rough bubble of gas ejected from a star as it goes into "retirement", casting off its outer layers and becoming a white dwarf. A planetary nebula is an expanding cloud of gas, so it has a limited lifespan, until the cloud gets to diffuse to see, or too far from the central remant of the star to shine in absorbed and reemitted light. this puts a clock on it of about one hundred thousand years. A long time as far as library fines go, but nothing on the time scale of stellar existences. There are therefore relatively few planetary nebulae (only four in Messier's list), and this is the hardest to see.

M101: Didymus

m = 7.70

Difficulty Level: 4 (Easy star hop, individually faint)

.........This galaxy is a large, face-on spiral, quite an impressive sight that will even allow you to see the spiral arms, but the night has to be pretty much perfect. On my excellent viewing night this week, I was able to star-hop to the correct field, and see all of the stars that I was supposed to see, but there was no sign of the galaxy. Stuff like this gave rise to my third law of living, "You can do nothing wrong, and still lose."

.........Messier 101 was named "Didymus" (by me) because it is its own twin, of a sort. Charles Messier recorded this galaxy as M101 and later recorded the same galaxy as M102. In the case of M40, Messier found something nearby and get it a number. In the case of the galaxy M91, in Virgo, Messier recorded a non-comet at a position where nothing was later found, and the number was simply assigned to another galaxy nearby that was bright enough to have been seen by Messier, but was otherwise unrecorded.

M108: Galaxy

M108: Galaxy

m = 10.10

.......... Both M108 and M109 are faint spiral galaxies that are difficult to observe when the night is not completely dark, and the sky is not completely clear. M108 can be found on the same star map as M97.

M109: Galaxy

m = 9.80

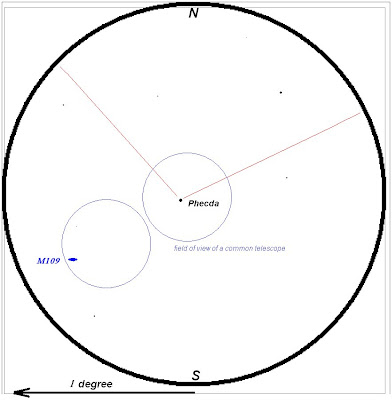

..........Both M108 and M109 are faint spiral galaxies that are difficult to observe when the night is not completely dark, and the sky is not completely clear.

Difficulty Level: 4 (Easy star hop, individually faint)

No comments:

Post a Comment