..........This entry is much later than I had hoped it would be, and it has grown into quite a monster in the meantime – I promise, this is larger than the standard entry will be, and much more space than the average constellation will get. Heck, I had to break Ursa Major in three parts! This is part I, "Ursa Major As a Guide to the Sky". The next two will be "Ursa Major, the Constellation" and "Ursa Major, Telescope Stuff". Posting frequency will drop to (probably) once per week in the fall, but I want to post more frequently in the summer. For example, I hope to finish Ursa Major this week.

Downloading

.........Much of the writing time between posting was directed to working out a way to make star maps that were done entirely by myself, so that I could replicate them as I would. However, once I post these as images, much of the detail gets lost; to correct this, I have uploaded the image files to a Google discussion group. (If you choose, you are free to ask questions about the blog, certain topics, or things that you would like to see there, but I would appreciate if you would comment about individual blogs in the space after the blog entry.) There, you may download the images to get maps that I hope you might find useful.

My Starting Point

.........There is

Naming Stars

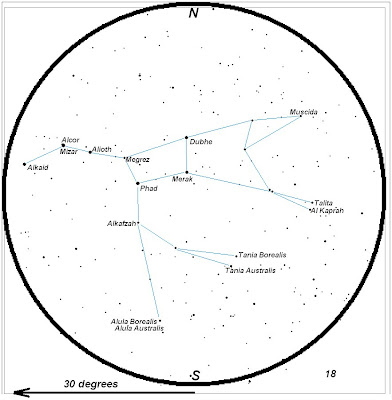

.........The Big Dipper can also serve to introduce how stars are tracked individually as well. Of all the stars that can be seen with the naked eye (there are slightly more than 5,000 as the HIPPARCOS satellites saw it), there are about two hundred that have individual names. These are typically the brightest stars in a constellation, and show the limits of the usefulness of designating stars individually in such a unique manner; after all, could you reliably remember five thousand names? (Heck, have you ever had to correct a grandparent or other family member? Odds are, there aren’t five thousand in the family.) Here is a star map of Ursa Major with all of the named stars shown: (at least, before people start claiming stars to name themselves.)

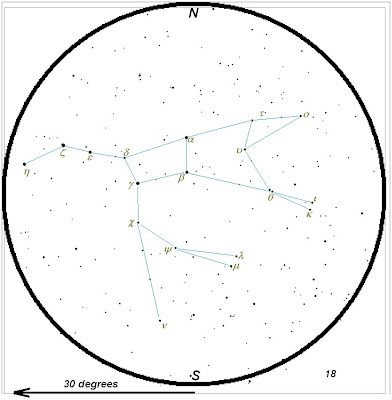

.........Another method was derived by Johann Hevelius in a star atlas published in 1603. He tried to name the brightest star in a constellation “alpha of that constellation”, so the brightest star in Ursa Major should be a Ursae Majoris (then b, g, d, and so on). Ursa Major is an unfortunate starting point for introducing this system, because in this case, as you can see, Hevelius simply started by making a pattern of the Big Dipper. Here is a map of the Big Dipper with stars named in this system:

.........The stars of the Big Dipper can also be used to provide a sense of scale across the sky. Judging scale is one of the biggest problems in getting used to moving around the sky, because in the sky there are no points of reference that we see on the ground. Fortunately, we have fairly reliable measurement tools at the end of our arms – we can use our hands. (Yes, your hands are almost certainly not the same size as mine, but your arms are also differently sized than mine as well. This balances out.)

.........The stars of the Big Dipper can also be used to provide a sense of scale across the sky. Judging scale is one of the biggest problems in getting used to moving around the sky, because in the sky there are no points of reference that we see on the ground. Fortunately, we have fairly reliable measurement tools at the end of our arms – we can use our hands. (Yes, your hands are almost certainly not the same size as mine, but your arms are also differently sized than mine as well. This balances out.) .........Consider the “distance” between the stars Dubhe and Merak. I put the word “distance” in  quotes, because we have to define what we mean by distance. If I describe the physical distance as 45 light years, how does that help you? We’ll use “distance” to refer to the angular distance between two things in the sky, so that an object on the horizon due north will be 180⁰ away from an object just above the horizon due south. In this way, the distance between these two stars is just a little bit more than five degrees. As shown in the diagram below, this distance against the sky is about the same as the angular size of three fingers held at arm’s length. This can also be used as an order to your bartender if the viewing isn’t good. (PARENTS: If you little one comes in, sighs, and says, “Gimme three fingers of Redpop”, then s/he has been reading this blog.)

quotes, because we have to define what we mean by distance. If I describe the physical distance as 45 light years, how does that help you? We’ll use “distance” to refer to the angular distance between two things in the sky, so that an object on the horizon due north will be 180⁰ away from an object just above the horizon due south. In this way, the distance between these two stars is just a little bit more than five degrees. As shown in the diagram below, this distance against the sky is about the same as the angular size of three fingers held at arm’s length. This can also be used as an order to your bartender if the viewing isn’t good. (PARENTS: If you little one comes in, sighs, and says, “Gimme three fingers of Redpop”, then s/he has been reading this blog.)

.........The stars Dubhe and Phad are ten degrees apart. This is about the distance between your fingertips is you extend your hand as shown below, a form that is either reminiscent of a certain arachnid-based superhero from a company with “marvelous” lawyers, or – if you were a young person in the 70’s or 80’s – the “secret devil sign” beloved by metal bands and freaked out middle-aged PTA moms. Of course, if a freaked-out PTA grandma sees you making a devil sign to the night sky, then you might need to refer back to the “three fingers” – once the police leave.

.........The stars Dubhe and Phad are ten degrees apart. This is about the distance between your fingertips is you extend your hand as shown below, a form that is either reminiscent of a certain arachnid-based superhero from a company with “marvelous” lawyers, or – if you were a young person in the 70’s or 80’s – the “secret devil sign” beloved by metal bands and freaked out middle-aged PTA moms. Of course, if a freaked-out PTA grandma sees you making a devil sign to the night sky, then you might need to refer back to the “three fingers” – once the police leave.

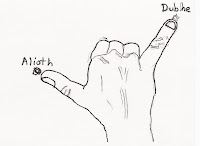

.........The stars Dubhe and Alioth are fifteen degrees apart, which can be measured by the hand sign below, which I have christened the “dude”. (Pronounced “duuuuuuuuude”.)

.........The Big Dipper can also be used as a guide around the sky as well. A line that passes through Merak and Dubhe will pass very close to the North Celestial Pole, and hence, the North Star. (This is helpful, because while the North Star Polaris is a reasonably bright star, it is nowhere near the brightest star in the sky, though this is a common misconception.)

........Get familiar with the Dipper and the stars around it, and I'll be back to write about the stars of the Dipper itself, and a famous test of vision across the ancient world.

........Get familiar with the Dipper and the stars around it, and I'll be back to write about the stars of the Dipper itself, and a famous test of vision across the ancient world.

No comments:

Post a Comment