“Thou art as opposite to every good

As the Antipodes are unto us,

Or as South to the Septentrion”

As the Antipodes are unto us,

Or as South to the Septentrion”

Henry VI, part III Act I, scene iv, lines 134-136

.........The first and last stop on our year-long tour of the constellations (at least the ones that can be comfortably viewed from mid-northern latitudes) will be Ursa Major. To be more familiar, I should be referring to Ursa Major as the Big Dipper, an asterism of the seven brightest stars in the constellation. (An asterism is a recognized pattern of stars that is not itself a constellation. In some cases as we will see later this summer, an asterism can include stars from more than one constellation.) I am following tradition in this as all of the early catalogs began with Ursa Major and Ursa Minor (again, more commonly recognized by the Big Dipper and Little Dipper).

.........The stars of the Big Dipper have been recognized as a constellation from the earliest times. Homer seems to have recognized the Big Dipper (as a bear) as the only circumpolar constellation as “Arctos, sole star (here taken as constellation) that never bathes in the ocean wave” The Big Dipper appears in the Bible, in the book of Job “He [God] made the Bear and Orion, the Pleiades and the constellations of the South (9:9)”, and “Can you bring forth the Mazzaroth in their season, or guide the Bear with its train (38:32)?” Note that the Dipper is not represented as a bear with an incongruously large tail, but as a bear with three followers (cubs? hunters?). (It is unknown what Mazzaroth represents. It could refer to a southern constellation using the pattern of parallelism in Hebrew poetry, or it could represent the zodiacal constellations as a set. It could also represent a handy gardening tool with a built-in mulching attachment; we just don’t know.)

.........In addition to being such an easy asterism to find in the sky, and in addition to leading the viewer to a number of other bright stars (hey, you have to learn the sky starting somewhere), the Big Dipper is one of the oldest constellations. I feel that I’m being fair in saying “the Big Dipper” here, as opposed to “Ursa Major”, because “Ursa Major” itself is an expansion of the Big Dipper. Sure, it was an expansion that took place several hundred years BCE while the other circumpolar constellations were created at this time, but the Big Dipper was old even at this time. It is impossible to know just how old, but the idea of the Big Dipper as a bear is surprisingly widespread, in bold defiance of the fact that it looks nothing like a bear. (The idea that Ursa Major is old enough to go back to a time in which bears looked a lot more like dippers has, unfortunately, little evidentiary support.) The writer Thomas Hood took a different tack:

“Imagine that Jupiter, fearing to come too nigh upon her teeth, layde hold on her tayle, and thereby drewe her up into the heaven; so that shee of herself being very weightie, and the distance from the Earth to the heavens very great, there was great likelihood that her taile must stretch. Other reason know I none.”

.........Our constellations are (largely) the Latin names of Greek constellations, many of which were taken from Babylon and India

.........There has been some conjecture that the Big Dipper is the remnant of some Paleolithic bear cult, but this might be reading too much into this. Beyond the elephant, the bear is the largest land creature, so the most important group of stars is probably predisposed to be called “the bear”. If there is anything to the idea that the Dipper was considered a bear even before the migrations to America, it might be as William Whitney (American philologist of the nineteenth century) supposed, looking at how the Sanskrit word Riksha can mean either “star” or “bear”, depending on the gender of the word. The seven most important stars in the sky could then have been the "seven bears", or just eventually lumped together as "the bear". Or, maybe a North America culture just picked "bear", and the constellation name spread. There is currently no way to know.

.........I was considering also discussing the number of times that different constellations appear in literature, but starting with the Big Dipper made this prohibitive, since references to it are so common. Perhaps my third pass through the constellations can cover its literary lights (see you in 2011). I'll tell you what: I'll cover the Bible, Shakespeare, Dante Aligheri, and Homer, and ask the gentle reader to take the rest. If you run across a literary reference to a constellation, please let me know. (I'll cite you -- you're name will be in a blog ... wow!) I did find three appearances of the Big Dipper in Shakespeare as well. In addition to the quote that begins this entry (the Septentrion, or “seven stars” is the Dipper), the Big Dipper is also referenced in Henry IV, Part I, where it is used as a timepiece (I'll discuss this more when we talk about the Little Dipper, and using the stars to the north as a clock) and a reference in King Lear where Shakespeare has one of the villains of the piece speak in what we would now consider to be enlightened skepticism about astrology. I'll go into more detail on this when I talk about the first zodiacal constellation on our tour -- Ophiuchus! (Don't recognize this as apart of the Weekly World News zodiac? I'll explain soon ...)

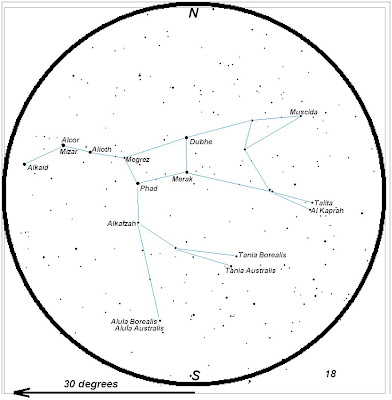

.........In this post, I'll speak about viewing Ursa Major with the eye, and add in binoculars and telescopes in the next blog. I have discussed in a previous blog entry how the two stars at the end of the bowl, Dubhe (which comes from its title as the back of the bear) and Merak (which comes from its title as the loin of the bear) can be used to find the North Star, Polaris. There are several other bright stars that can be found using the stars of the Dipper as well.

.........Confining ourselves to the stars of the constellation itself, take a look at the center star of the handle, the bright star Mizar. Mizar has a magnitude of 2.23, a fairly bright star. Close to Mizar in the sky, close enough to be seen with the eye, if your eyes are good, and easily with a pair of binoculars, is a fainter star, Alcor. Alcor has a visual magnitude of 3.99, which means that we are receiving about five times as much light from Mizar as we are from Alcor; we don't see Mizar as five times as bright, because our eyes don't work such that twice the light equals twice the brightness. If that were true, then your head would all but explode as you went inside and turned the lights on after being out looking at the stars!

.........Mizar and Alcor are separated by a distance in the sky that is about 1/3 the apparent size of the Moon in the sky. Many cultures have used this star as a test of vision, requiring a reasonably sharp eye to see this as two stars and not one. There has been a question as to whether Mizar and Alcor are actually part of a double star system, or if the are simply close to the same line of sight in the sky. This is somewhat similar to seeing two people sitting together on a bus and assuming that they are married. It does seem that these two stars are indeed orbiting each other, but widely separated. The closer star, Mizar is about 78 light years away, which means that the light you see tonight left the star's surface in early June in 1931, and has spent all that time traveling through space. Alcor is about three light years away from Mizar, or about 190,000 times the distance between the Earth and the Sun. If these stars are orbiting each other, it will take about 43 million years for each orbit. Mizar is itself a double star, but you will need a telescope to see that. Both stars are about the same brightness, and much closer. They orbit each other in only about 104 days, a much smaller separation.

........The next post will take us through Ursa Major with binoculars and telescope, and we will see if we can then move on to another constellation.

SPECIAL ADDITION: Check out this link!

No comments:

Post a Comment