.........Yesterday was the fortieth anniversary of the Moon landing, the first of the only six times in history that humans have actually walked on

another planetary body. I was a little less than two when this happened, and by the time my youngest brother was born we had left the Moon, and we haven't been back since.

another planetary body. I was a little less than two when this happened, and by the time my youngest brother was born we had left the Moon, and we haven't been back since..........There have been a number of responses that I have seen to this fact. One of the drives for reaching the Moon was to "win" the space race against the Soviet Union. Once this was done, this part of the impulse was gone. We had already run this race, why stand around at the finish line instead of going out for pizza and beer? (That would be "root beer" if you're under twenty-one.)

..........Ratings for even the second Moon landing were well below that of the first, and it seemed as if there was no enthusiasm among the general population for more Moon shots. The Lunar program was also seen as a Democratic program (the landing was just six months after Nixon's inauguration), and it might have suffered from this view under Nixon and Ford. After Apollo 17, the space program turned to the shuttle, seen as preparation for a next step, but which seemed to become its own destination. Even the space station has been its own end. What next? Are we as far as we can go? Are we as far as have the will to go?

..........Another question that is asked concerns our use of resources, and this is certainly not an idle or non-compelling question, especially now. What could we do with the money that space exploration or NASA in general uses with people in poverty, desperate need of health care, and the job market dropping like the morale of a football team once Terrell Owens signs up?

..........Also, we must consider the question of priorities, even if we can assume that amount of money going into space science. Is it good to fund manned missions, or should we use the same money to fund a number of smaller efforts, in which a greater number of people can take part?

..........All of these questions demand a good answer, and I will even go so far as to say that in order to support more manned missions, an argument must be made that justifies a program against all of these points. Can a space program do more than just beat "the enemy" somewhere, and produce more in the public imagination beyond Tang (TM)? To make this argument, I want to make a wider claim about what the Moon landing provided.

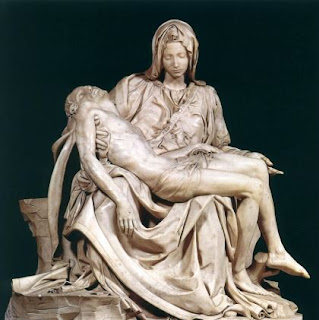

..........Consider the object shown to the left. What is the value of this? Is this simply a waste of good marble that could have been ground up and used as the basis for houses, sewers, roads, etc? Is the value of this equal to the value of the material that makes it up, or the use to which the material could be put? I will venture to say that most people would say "no" to the last few questions, to acknowledge that art as a human creation has a value in the act of cultural, human expression. That beyond the day to day needs of basic human existence, we have a need that is higher, to make a higher purpose, a reason why we are here, a calling to others to acknowledge something even higher to which human beings can aspire. Even art taken as entirely secular still speaks to the fundamental human desire to define meaning for ourselves, to create ourselves as some thing above day-to-day existence. The Moon landing also made the argument that human beings can create a meaning for themselves in an even wider fashion. The statue I picked was the work of one man's genius, but the Moon landing required scientists to plot the way there, engineers to create the materials we needed to get there and back, and what we needed to keep people alive on the trip, people brave enough to risk everything on the say-so of people who had never done this before and the skills to handle what could come up, and taxpayers.

..........Consider the object shown to the left. What is the value of this? Is this simply a waste of good marble that could have been ground up and used as the basis for houses, sewers, roads, etc? Is the value of this equal to the value of the material that makes it up, or the use to which the material could be put? I will venture to say that most people would say "no" to the last few questions, to acknowledge that art as a human creation has a value in the act of cultural, human expression. That beyond the day to day needs of basic human existence, we have a need that is higher, to make a higher purpose, a reason why we are here, a calling to others to acknowledge something even higher to which human beings can aspire. Even art taken as entirely secular still speaks to the fundamental human desire to define meaning for ourselves, to create ourselves as some thing above day-to-day existence. The Moon landing also made the argument that human beings can create a meaning for themselves in an even wider fashion. The statue I picked was the work of one man's genius, but the Moon landing required scientists to plot the way there, engineers to create the materials we needed to get there and back, and what we needed to keep people alive on the trip, people brave enough to risk everything on the say-so of people who had never done this before and the skills to handle what could come up, and taxpayers. ..........Lots of taxpayers. On the other hand, this enabled everyone in the country to take pride in and ownership of the Moon landing, and justifiably so, in my opinion. This, I would say, is something that we need again now.

..........When John F. Kennedy called for human exploration of the Moon, the United States was in an excellent position to commit ourselves to a great leap, a tremendous effort that we could do because the US was at the zenith of its power. The recovery of the rest of the world, directly affected in World War II, was still at the point where they were a tremendous market for the rest of the world, and had not yet returned to the production capacity that the rest of the world had before. Today is drastically different, but a space program with a clear human goal of a sustained presence on the Moon or a trip to Mars could restore not military leadership, not technological (though it would help) leadership, but leadership of vision. I can most honestly speak of this in terms of what the space program meant to me.

..........What did the landing on the Moon mean to me? I didn't gain an interest in astronomy when I was one and a half, but over the next few years I do remember watching the astronauts returning to Earth, and being recovered by aircraft carriers (yes, Keith, I know those were SEALs), and I can remember my amazement at considering that people, actual people, were capable of firing a rocket (essentially a big, controlled bomb) off from the Earth, using it to send people into space, and then being able to work out where they would come back with such accuracy that there could be ships waiting right there to pick them up. As the seventies aged, I saw a rush of people for magic, whether it was transcendental meditation, astrology, weird new medical fads in which people hoped for some way of cheating of the universe, some way of the controlling it to get the result they wanted. I was not brought up to be "afraid" of math, as if math was some magical field that only special people could do, so even at seven I was confused about why people would turn away from the examples of all the best that we could do to trust in something with no results, but which felt nicer, as if you could ask the universe for something, and how much you believed, or how nice you were actually counted. People have even sidestepped what human beings can do to hope to jump past them, to imagine aliens visiting the Earth who will solve all of our problems if we just ask them nicely enough.

..........There is no evidence of that ever happening, and no evidence of any magic, or any space cavalry to come riding over the hill and save us from the problems that we made for ourselves. All we have is us. We have problems that we cannot solve simply by saying, "I'm fine; let each person solve this independently." We have problems that cannot be solved state by state, and now even nation by nation. As we need to work together (not *under* each other, but as a collection of individuals/localities/states/nations) we should have something that will give us an experience of true greatness, something that needs all of us to work together, and shows us that we can do what seems impossible, to give the renewal of will and the hope that our more tractable problems like disease, poverty, hunger, etc., ad infinitum, are within our reach themselves.

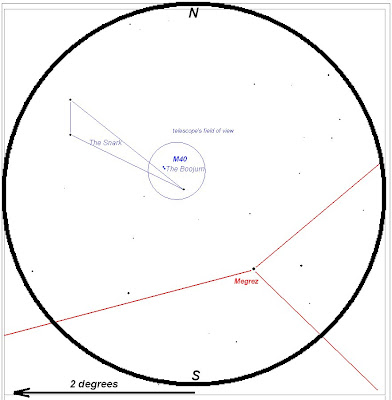

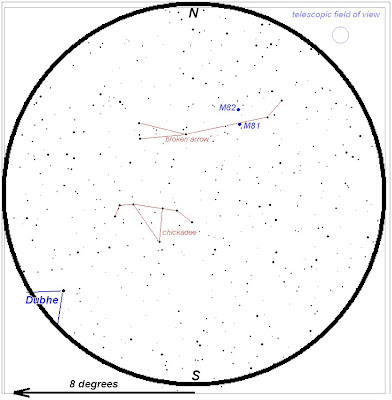

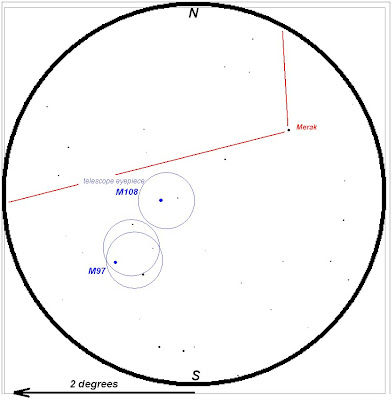

M108: Galaxy

M108: Galaxy

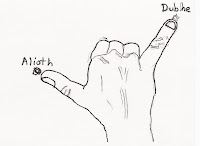

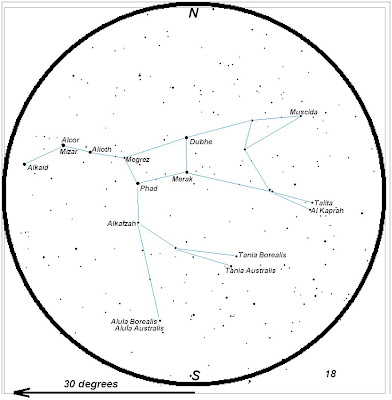

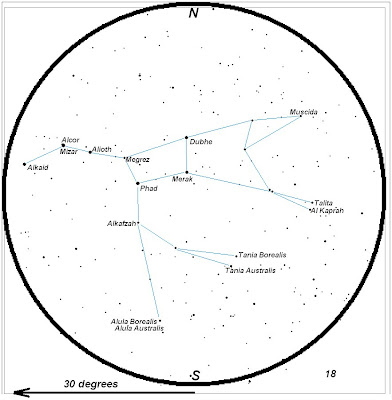

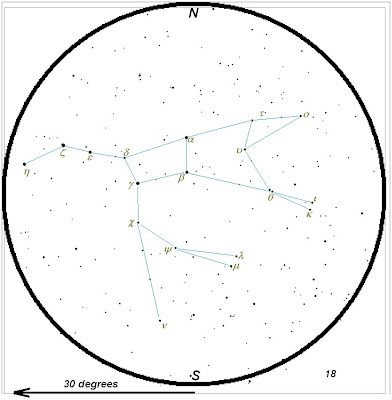

.........The stars of the Big Dipper can also be used to provide a sense of scale across the sky. Judging scale is one of the biggest problems in getting used to moving around the sky, because in the sky there are no points of reference that we see on the ground. Fortunately, we have fairly reliable measurement tools at the end of our arms – we can use our hands. (Yes, your hands are almost certainly not the same size as mine, but your arms are also differently sized than mine as well. This balances out.)

.........The stars of the Big Dipper can also be used to provide a sense of scale across the sky. Judging scale is one of the biggest problems in getting used to moving around the sky, because in the sky there are no points of reference that we see on the ground. Fortunately, we have fairly reliable measurement tools at the end of our arms – we can use our hands. (Yes, your hands are almost certainly not the same size as mine, but your arms are also differently sized than mine as well. This balances out.)