.....What is the Zodiac? Well, the ecliptic is the path that the Sun takes through the sky, and the planets all stay within 7° of this line (If we skip Mercury, all the planets are within half this distance of the ecliptic). The ecliptic passes through twelve constellations (traditionally; as the constellations were given boundaries by the International Astronomical Union in 1930 the ecliptic passes through thirteen constellations), and these constellations are the Zodiac. Besides being the only zodiacal constellation with no Messier objects, Libra is also the only zodiacal constellation named after an inanimate object.

.....What is the Zodiac? Well, the ecliptic is the path that the Sun takes through the sky, and the planets all stay within 7° of this line (If we skip Mercury, all the planets are within half this distance of the ecliptic). The ecliptic passes through twelve constellations (traditionally; as the constellations were given boundaries by the International Astronomical Union in 1930 the ecliptic passes through thirteen constellations), and these constellations are the Zodiac. Besides being the only zodiacal constellation with no Messier objects, Libra is also the only zodiacal constellation named after an inanimate object......Our constellations can be traced back to the forty-eight the Greeks had (there are eighty-eight constellations now), but the constellations of the Zodiac are much older. This makes sense because while many of the constellations can be thought of as “sky-decorations” the Zodiac allowed the ancients to track the seasons. Of the zodiacal constellations, Libra might one of the youngest.

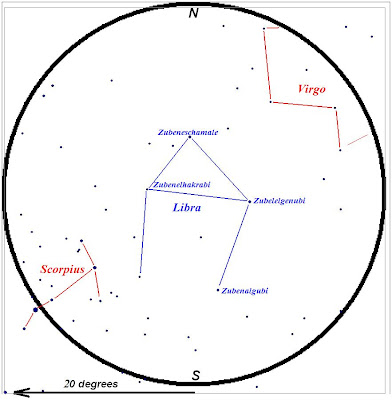

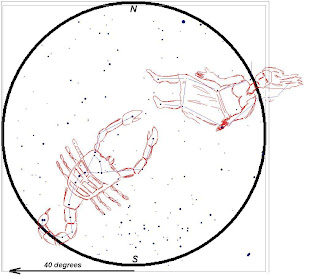

.....Libra as the balance represents that the Sun would be in this sign at the Autumnal Equinox, when the day and night would be equal lengths, or at least it was. According to the boundaries as they are now, the Sun would be in Libra at the equinox from about 2200 BC until about 700 BC. Even when not using the strict modern boundaries, the wobble of the Earth around its axis (which I discussed in a post on Ursa Minor) would have carried the equinox into Virgo, where it is now (and where it will be until AD 2450). This seems to indicate that Libra as a scales must have existed when the equinox was well inside Libra, but there are many references to these stars as Chelae, the claws of the scorpion. First, as seen below, the stars of Libra work well as the claws of the scorpion, whereas with Libra as a scales, the scorpion’s claws seem a little pathetic. The (seriously cool) names of the stars could refer to this, with Zubeleschamale translating as “the northern claw” and Zubelelgenubi as “the southern claw”. This is contested in some sources (alright, I admit it – in an unsourced article on Wikipedia) in that the Arabic (zubānā) and Akkadian (zibanitu) words for “scorpion” and “scale” are the same. Life becomes more complicated with the constellation having either four claws or four scales, but Richard Allen’s Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning considers Zubelalgubi as a degenerate version of the name “Zubelelgenubi”, and Zubenelhakrabi (the scorpion’s claw) as belonging to g Scorpii, which was apparently due to a need to invent two new claws when the other ones became Libra.

.....Why were the scorpion’s claws made into the balance of Libra (assuming, of course, that this is what happened)? Sure, there would be pressure to have twelve constellations on the Zodiac, one per month, and the reason of having a balance at the point where day and night are balanced make sense, but I have another idea why an inanimate object was added to the Zodiac where it was …

.....Why were the scorpion’s claws made into the balance of Libra (assuming, of course, that this is what happened)? Sure, there would be pressure to have twelve constellations on the Zodiac, one per month, and the reason of having a balance at the point where day and night are balanced make sense, but I have another idea why an inanimate object was added to the Zodiac where it was … Five minutes before the first sexual harassment lawsuit

Five minutes before the first sexual harassment lawsuit.....Unfortunately, Libra is pretty boring as far as deep-sky objects are concerned. There are no open clusters or nebulae in Libra, and the galaxies and one globular cluster in Libra fall far from being easy to find. I’ll address these on my next pass. Zubenelgenubi is a fairly easy double star to split, with the companion star being dimmer, but not tremendously dimmer (magnitudes of 2.8 and 5.2), and about 4 minutes of arc apart, or about one-eighth the size of the Moon in the sky. I could split this double star with a pair of binoculars, so this represents an excellent opportunity to do the same, and take the first step towards learning how to observe and split double stars.

.....The second constellation that I’m looking at in this post is the Northern Crown, Corona Borealis. If I may digress for just a moment, when I was much younger, carrying my telescope out to an extraneous plot of land behind our house, one of our neighbors asked me about what constellations were visible, and when I got to this one, he said,” No. That’s not it. I’ve seen that before and that’s not it!!!” (He didn’t shout, but he was speaking very definitively and I’ve learned that nothing is more definitive on the internet than using three exclamation points.) I realized pretty quickly that he was thinking about the northern lights, the *aurora* borealis, but I cannot remember if I tried to explain that, or just thought, “Whatever, old dude” (or whatever the early 80’s version of that was) and went on.

.....The second constellation that I’m looking at in this post is the Northern Crown, Corona Borealis. If I may digress for just a moment, when I was much younger, carrying my telescope out to an extraneous plot of land behind our house, one of our neighbors asked me about what constellations were visible, and when I got to this one, he said,” No. That’s not it. I’ve seen that before and that’s not it!!!” (He didn’t shout, but he was speaking very definitively and I’ve learned that nothing is more definitive on the internet than using three exclamation points.) I realized pretty quickly that he was thinking about the northern lights, the *aurora* borealis, but I cannot remember if I tried to explain that, or just thought, “Whatever, old dude” (or whatever the early 80’s version of that was) and went on.