Caesar: …” I am as constant as the northern star,

Of whose true-fix’d and resting quality

There is no fellow in the firmament.

The skies are painted with unnumber’d sparks,

They are all fire and every one doth shine,

But there’s but one in all doth hold his place”

Julius Caesar, Act III, scene I, lines 60-65

…..Shakespeare was a hack. More on this later.

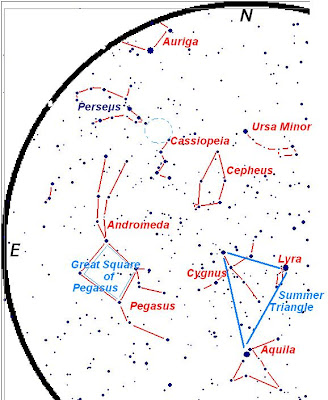

…..A blog on Ursa Minor, the Little Dipper, is going to demand that I go pretty far afield to try and make this interesting because this is a pretty inconsequential constellation. The Little Dipper is probably the most famous constellation that almost no one can find. The constellation is always above the horizon literally until you reach South America as you go south, but except for the three brightest stars, including the Pole Star, Polaris, the rest of the constellation is so faint that it can be lost under pretty much any background light.

…..Ursa Minor, quite frankly, has its name write a check most of its stars can’t cash. The constellation would be quite ignorable if it were not for the star Polaris, and from Greek times to the Renaissance this constellation was sometimes referred to as “

Cynosura” (what a translation to this word means is not known, but it probably has something to do with a dog) and sometimes that name only referred to the brightest star in the constellation, so for most of human history the general reaction to the constellation is, “The heck with it, just deal the bright, useful star.” (A reasonable question might also be “Why not just call it, like, “Polaris” or something that shows that since it’s by the Pole, and this brings us to one of Shakespeare’s mistakes. Again, more on this a little later.)

.....Polaris has its name because it is very, very close to the North Celestial Pole. To see why this is doubly lucky, let’s look for a moment at how the sky appears. Obvious statement of the day: the stars are all very, very far away. So far away that even as they move through space, a time traveler stepping from a clear night in first dynasty Egypt to tonight would only notice a shift in a handful of the stars with respect to each other, and even then only if that time traveler had some pretty good measuring tools. Because of this, it is useful to treat the sky as a dome, or as a globe that we see the inside of from the Earth. To map this, we use the Earth to help us. Consider the Earth as spinning inside this gigantic sphere; one thing that we could "see", projected against the heavens would be the sky appearing to turn as we spun beneath it. Projected on the sky, we could trace north and south poles above the Earth's north and south poles (called the North and South Celestial Poles, reasonably enough), and the Celestial Equator above the Earth's equator. The North Celestial Pole is less than half a degree of arc away from Polaris, so if you were to sit and watch the sky over the course of a night (an

eminently worthy endeavor), the stars would appear to whirl around the sky, with only Polaris remaining still. (The South Celestial Pole has no stars of note anywhere near it.)

.....Even Polaris has gotten a reputation beyond its actual means. Because of the usefulness of Polaris, (perhaps) the true idea that Polaris will help you find where you are has led to the (false) idea that Polaris is inordinately easy to find. As I discussed in my post on the

Big Dipper, and repeated in my map on the previous post, Polaris can be identified by using the two stars at the end of the bowl of the Big Dipper (which

is relatively bright), but a surprisingly common misconception is that Polaris is the brightest star in the sky. How this came about, I certainly don't know. (Polaris is actually the 47

th brightest star in the sky.) This has led one friend of mine to increase the "Don't Get No Respect" quotient for this constellation by arbitrarily and willfully defining the brightest visible star as "the North Star". (Hi, Trish!)

…..Besides the three brightest stars, the others are fourth, fourth, fourth, and fifth magnitude, this definition of brightness stretching back to the ancient Greeks when the astronomer Hipparchus divided the stars by their brightness, ranking the stars from “first rank” (the brightest) to “sixth rank” (the dimmest). The other stars that observers expect to see from the constellation figure are dim enough so that a hazy evening, a bright Moon, or the ubiquitous nearby

Wal-Mart (in case you

didn’t think that

Wal-Mart was evil enough) will make these stars impossible to see. In seventh grade, when I got my first chance to study astronomy institutionally, one of our assignments was to sketch constellations we found in the sky. I saw a lot of students turn in the Little Dipper, but none of them got the right stars, a trend that I notice up to today. (A second thing is that I notice

Wal-Mart is apparently in Microsoft’s spell-checker; Scorpius: No,

Capricornus: No,

Wal-Mart: yes – be afraid, be very afraid …)

.....Going back to that hypothetical time traveler, however, the sky as a whole would have shifted noticeably, because the Earth does not sedately simply rotate on its axis, that axis is tracing out a circle on the sky like a tremendous top, with a period of 26,000 years. This wobble is now pointing at Polaris, getting even closer as this century goes on, but in Julius Caesar's time, Polaris was more than ten degrees away from the pole (the "

Secret Devil Sign", in memory of the recent death of

Ronnie James Dio), making a definite loop during the night. Our time traveler would have seen

Thuban (also on the map) as the North Star, and if you wait for about 13,000 years you will see Vega, in Lyra, as the pole star, and that truly is one of the brightest stars in the sky. This is Shakespeare's astronomy mistake in Julius Caesar.

….As far as anachronisms in Shakespeare go, though, this one is not the biggest, even in that play. In Act II, scene i, line 191, Brutus says “Peace! Count the clock.”, and in Act II, scene ii, lines 114-115, Caesar asks “What is’t o’clock?”, to which Brutus responds, “Caesar, ‘

tis stricken eight.” Mechanical clocks in the time of Caesar (actually invented in the thirteenth century AD) would actually be

less of an anachronism than, say, giving Macbeth Iron Man’s armor…

“Is this a transistor I see before me, the bipolar junction toward my hand?”

“Is this a transistor I see before me, the bipolar junction toward my hand?”.....Oh sure, you might say that Shakespeare didn't know any better but he was able to come up with more appropriate way to discuss time earlier in the scene I just quoted, when Brutus says "I cannot, by the progress of the stars,/ Give guess how near to day." - lines 2-3.

…..Ursa Minor is an important place being filled by a rather boring occupant that is still bright enough to fulfill a useful purpose. (Like Al Gore - Zing!) Yes, I know that this would have been funnier ten years ago. Let me try this again ...

…..To sum up, Ursa Minor is a dim, dark, empty place with only a couple of bright points – kind of like Lower Michigan (Double Zing!)

.....The Moon enters the umbra, the central shadow at 12:51 AM (again, CST, the best time zone) , and totality, with the Moon entirely in the umbra from 1:57 AM to 3:14 AM. On Earth, a total eclipse is completely dark, but in a lunar eclipse the light passing through the Earth's atmosphere is scattered into the shadow. In the same way that the sky appears blue because blue light is scattered first, and the setting Sun appears red because red light is scattered last, the totally eclipsed Moon will appear a deep red, sometimes getting so faint that the full &^$%&^% Moon is hard to find in the sky.

.....The Moon enters the umbra, the central shadow at 12:51 AM (again, CST, the best time zone) , and totality, with the Moon entirely in the umbra from 1:57 AM to 3:14 AM. On Earth, a total eclipse is completely dark, but in a lunar eclipse the light passing through the Earth's atmosphere is scattered into the shadow. In the same way that the sky appears blue because blue light is scattered first, and the setting Sun appears red because red light is scattered last, the totally eclipsed Moon will appear a deep red, sometimes getting so faint that the full &^$%&^% Moon is hard to find in the sky.

.....The only stars brighter than Vega are Arcturus (just barely), Sirius (a winter star), and Canopus and

.....The only stars brighter than Vega are Arcturus (just barely), Sirius (a winter star), and Canopus and

.....Here is how this works, if you know the phase of the Moon, or when the new and/or full moon is that month (you can find these on many calendars, plus, I will now begin posting that information at the beginning of each month. For August, 2010:

.....Here is how this works, if you know the phase of the Moon, or when the new and/or full moon is that month (you can find these on many calendars, plus, I will now begin posting that information at the beginning of each month. For August, 2010:

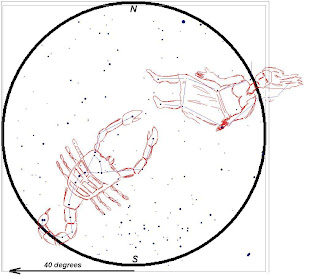

.....The second constellation that I’m looking at in this post is the Northern Crown, Corona Borealis. If I may digress for just a moment, when I was much younger, carrying my telescope out to an extraneous plot of land behind our house, one of our neighbors asked me about what constellations were visible, and when I got to this one, he said,” No. That’s not it. I’ve seen that before and that’s not it!!!” (He didn’t shout, but he was speaking very definitively and I’ve learned that nothing is more definitive on the internet than using three exclamation points.) I realized pretty quickly that he was thinking about the northern lights, the *aurora* borealis, but I cannot remember if I tried to explain that, or just thought, “Whatever, old dude” (or whatever the early 80’s version of that was) and went on.

.....The second constellation that I’m looking at in this post is the Northern Crown, Corona Borealis. If I may digress for just a moment, when I was much younger, carrying my telescope out to an extraneous plot of land behind our house, one of our neighbors asked me about what constellations were visible, and when I got to this one, he said,” No. That’s not it. I’ve seen that before and that’s not it!!!” (He didn’t shout, but he was speaking very definitively and I’ve learned that nothing is more definitive on the internet than using three exclamation points.) I realized pretty quickly that he was thinking about the northern lights, the *aurora* borealis, but I cannot remember if I tried to explain that, or just thought, “Whatever, old dude” (or whatever the early 80’s version of that was) and went on.