Welcome to another somewhat introductory posting, (this is why the posts are still in negative numbers), but one that can hopefully enhance your stargazing straightaway. One of the websites that I have listed among my links is to a site called “

Heavens Above”. I’m going to go into more depth on some of the benefits of this site, because it can provide location-specific star maps, and because of its satellite observing tools.

The space around the Earth has become pretty crowded in the fifty-plus years in human-made satellites have orbited the planet. It is a rare clear night on which even a casual observer does not notice an unblinking point of light tracing it way quickly across the sky. Satellites do not give off their own light, but can only be seen due to reflecting the Sun’s light. Given the small size of most satellites, this explains why even those in low orbits (about 600 km, or 360 miles, above the surface of the Earth) are faint when we see them. However, some satellites such as the

Hubble Telescope and especially the

International Space Station (ISS) can appear to be as bright as the brightest planets because they are in the lowest orbit (so rockets and shuttles from Earth can reach them economically) and both have large solar panels to provide their power, serving also as tremendous mirrors. These satellites can appear brighter than the brightest star, and even brighter than the brightest planet.

As it turns out, summer is an excellent time for observing satellites, even beyond the observation that for many people summer is a much more comfortable time to be outside. The reason for this has to do with the way that satellites are seen. In the diagrams shown, the Earth is drawn as a circle, and the orbit of a satellite orbiting the Earth is shown as a slightly larger circle. (Okay, this assumes a completely polar orbit – an orbit that takes satellites over the poles – but that isn’t too bad of an assumption and it exaggerates the size of a low-Earth-orbit satellite’s orbit. If the radius of the Earth is ten units, then the radius of the Hubble of the ISS is eleven units.) Since satellites are only seen from reflected sunlight, a satellite is only visible when it can see the Sun, but we (on the ground) can’t.

In the summer, as in the diagram on the right, we have short nights because the North Pole is tilted towards the Sun, which also allows much more of a satellite’s path to be visible. The thicker curve demonstrates the arc of the satellite’s orbit during which it is visible from our observing location. (The orange lines represent sunlight. The Sun is far enough away from the Earth that the Sun should best be thought of as a direction, not a point.)

In the winter, when the North Pole is tilted away from the Sun (this is not the Earth wobbling, it is tilted, rotating at an angle to its orbit) we have longer nights, and satellites are visible for less of their time above our horizon. Again, these diagrams are exaggerations, but the differences between the two seasons are still distinct.

To use the tools on Heavens Above, I set up a generic account for this blog, with a number of locations already specified. Once you are at Heavens Above, look under the “Configuration” heading for “Registered User Login” or “Create New Account”. (If the Heavens Above site has one problem, it is the sheer density of options available as a big, long column on the left.) Let’s start at the top under “Configuration”: while you could start by making your own account through “from database”, let’s start by looking at the Messier Pro account. Please click “Registered user login”. The login name I’ve set up for this is “Messier Pro” (yes, there is a space in the middle), and the password is “Hi Harry” (there is a space, and case does not matter). Now you will go to the home page for this account. (The default position for the observing location is Winona, Minnesota; if you don’t live there, click on the first active link under “Configuration” and change your location. I’m starting with Winona and Elbow Lake Minnesota; Green Bay, Wisconsin; Stephenson, Michigan; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Chattanooga, Tennessee; Knoxville, Tennessee; and Orlando Florida. If you aren’t in one of these places, feel free to add you own location to this list. (Sure, you could always just start your own account, but then we wouldn’t be “hanging out” together on line.)

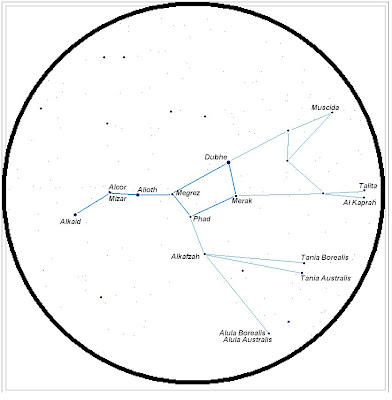

There are many options you have from this point; I am just going to describe two now. If you scroll down past “Configuration”, and “Satellites” to “Astronomy”, a few lines down is the option “Whole sky chart”. If you click on this you will be taken to an image of the sky as seen from your location, right now. You can change the entries below the chart to adjust for any time and date, a handy feature.

You can also use this website to find times when bright satellites will be visible. Under “satellites” (no surprise), you can find times to see bright satellites including the Hubble Telescope and the International Space Station, as well as fainter satellites (including the toolbag that was dropped from the ISS some time ago), as well as finding all satellites brighter than a certain limit (the smaller the magnitude the brighter the object – I’ll explain this in my next post). To find a certain satellite, click on the link of your choice. This takes you to a table of visible passes. You can then click on the date to get more details, as well as a map of the path across the sky.

Suppose that you see a satellite, and want to identify it. Well, if I saw a satellite last night and thought to take note of the time and the path, I could click on the “Daily predictions for all satellites …” of my choice, click on “Previous PM” at the top, and work through the satellites of the last night to identify the one that I saw.

As an example, here are the next bright (brighter than any stars out at the time) passes for the International Space Station for each of the locations on the list:

Starting in the Upper Midwest:

Winona, Minnesota:

On Saturday, June 20th, the ISS will appear just over the southwestern horizon at 4:59 AM, stay relatively low to the horizon crossing into the southern sky, then the eastern sky through Capricornus, Aquarius, Pisces, and Cetus, to set in the constellation of Taurus.

Elbow Lake, Minnesota

Not surprisingly, the timing in this list is the same as the Winona pass, although these two towns are far enough apart (Minnesota is a tall state) that Elbow Lake can’t see several of the Winona passes as the path of the satellite over the next week or so will south of Winona more often than north. The ISS will appear at 4:59 AM in the south and hug the horizon to set just north of east. I wouldn’t suggest dragging the family out of bed on a Saturday morning to show them this.

Green Bay, Wisconsin

Green Bay is far enough away from Minnesota to see totally different passes. The ISS will get to about as bright as the brightest stars on these passes, the brighter starting at 3:50 AM on Sunday, June 21st. Like Winona and Elbow Lake, the orbit of the ISS when it passes over Wisconsin will result in the satellite appearing in the south and hugging the horizon to set in the east. At its best the ISS will not be more than 14 degrees above the horizon (overhead is 90 degrees). Sleep in.

Stephenson, Michigan

This is a really bad week to try and see the ISS from the UP of Michigan. The best view comes at 3:33 AM on Wednesday, June 24th. Not a lot to get out of bed for, but the ISS will pass close to Venus and Mars in the morning sky.

In the East:

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Again, more morning passes, although if you do have the will to get up for 4:50 in the morning, the ISS will be the brightest point in the sky, it will go almost directly overhead from the southwest to the northeast, it will be visible for nearly eight minutes, and it is a good way to identify the Northern Cross and Cassiopeia.

In the Southeast:

Chattanooga, Tennessee:

As in Winona, all of the bright passes of the ISS will be in the predawn morning. Sorry. However, if you get up on the morning of Sunday, June 21st, at 4:50 in the morning, the ISS will appear close to directly overhead, pass through Pegasus, Andromeda, and Perseus to set in the northeast three minutes later. Yes, this is early in the morning, but it might be the best opportunity on this list.

Knoxville, Tennessee

Still morning passes as we move back to the south, but if you can pull yourself out of bed at 5:33 AM on Friday (June 19th) morning, you’ll have a great view of the ISS covering pretty much the whole sky, appearing in the southwest and setting in the northeast. The pass lasts for about five and a half minutes and gets 67 degrees above the horizon. (The pass of Sunday, June 21st starts at 4:50 with the ISS appearing close to overhead and setting in the northeast.)

Orlando, Florida

It seems that all of the US just gets morning views for the next week, but if you are up at 5:09 on Thursday (June 18th), then you can see the ISS appear high in the south southwest (very close to the planet Jupiter, the only really bright thing in the southern sky) and travel to the northeast.

NEXT POST: Where to find the planets right now!

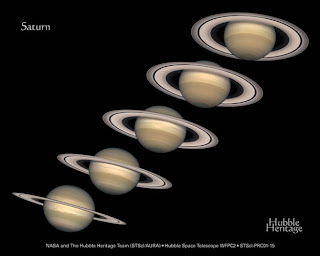

of the ring system is over one hundred and twenty thousand miles across – but the rings are only a few miles thick. We can see the rings of Saturn because Saturn’s orbit is tilted slightly compared to the Earth’s, but even with a tilt, there are still two times during Saturn’s orbit around the Sun at which Saturn is in the same plane as the Earth and we look at Saturn’s rings edge on. At these times, the rings seem to vanish altogether! The next time this happens will be in late September, but Saturn will be too close to the Sun to see, so go ahead and look now, if you have even a small telescope, to see Saturn’s rings as a narrow line.

of the ring system is over one hundred and twenty thousand miles across – but the rings are only a few miles thick. We can see the rings of Saturn because Saturn’s orbit is tilted slightly compared to the Earth’s, but even with a tilt, there are still two times during Saturn’s orbit around the Sun at which Saturn is in the same plane as the Earth and we look at Saturn’s rings edge on. At these times, the rings seem to vanish altogether! The next time this happens will be in late September, but Saturn will be too close to the Sun to see, so go ahead and look now, if you have even a small telescope, to see Saturn’s rings as a narrow line.

That’s all we have in the evening, but if you are actually getting up early some morning to look for the space station, or if you just have a time when you can’t sleep, the planet Jupiter (the fifth planet, and the largest planet in the solar system) will be high in the southern sky, and Jupiter will be by far the brightest thing in the area. If you were to look at Jupiter in even a small telescope, the four largest moons of Jupiter (on the same size scale as our own Moon) will appear as a line of stars. The planet Neptune (the eighth planet, about four times the radius of the Earth) is actually very close to Jupiter in the sky right now. If you are able to find Jupiter in a telescope, and you can tear yourself away from the view of the moons, and the bright bands and dark zones of Jupiter’s cloudtops, then you can try and find the planet Neptune to the north and east of Jupiter. Neptune is fainter even than the moons of Jupiter, and shows you as little. While telescopes will show the disk of the planet Neptune, and you can see the strong blue color caused by the methane clouds of Neptune’s atmosphere, that’s all that you get. No matter how strongly you magnify that image, neither Neptune nor Uranus (a little harder to find) will show any features whatsoever. Mark off that you have seen Neptune (hurrah!) and go back to Jupiter.

That’s all we have in the evening, but if you are actually getting up early some morning to look for the space station, or if you just have a time when you can’t sleep, the planet Jupiter (the fifth planet, and the largest planet in the solar system) will be high in the southern sky, and Jupiter will be by far the brightest thing in the area. If you were to look at Jupiter in even a small telescope, the four largest moons of Jupiter (on the same size scale as our own Moon) will appear as a line of stars. The planet Neptune (the eighth planet, about four times the radius of the Earth) is actually very close to Jupiter in the sky right now. If you are able to find Jupiter in a telescope, and you can tear yourself away from the view of the moons, and the bright bands and dark zones of Jupiter’s cloudtops, then you can try and find the planet Neptune to the north and east of Jupiter. Neptune is fainter even than the moons of Jupiter, and shows you as little. While telescopes will show the disk of the planet Neptune, and you can see the strong blue color caused by the methane clouds of Neptune’s atmosphere, that’s all that you get. No matter how strongly you magnify that image, neither Neptune nor Uranus (a little harder to find) will show any features whatsoever. Mark off that you have seen Neptune (hurrah!) and go back to Jupiter.