Sunday, December 13, 2009

The Geminid Meteor Shower

Sunday, November 8, 2009

A Bright Space Station in the Evening

.....Oh, one thing that I have not mentioned is that these bright passes will take place in the early evening, and will be very easy to see. I took the opportunity to find a (hopefully) good night for a number of cities of friends, family, and a couple of people who have actually admitted reading this thing. I looked at the Weather Channel’s website, picked nights predicted to be clear, and noted the time and directions to look. I’ve put these in alphabetical order by state. If you’re state isn’t in here, then look at a nearby city, or drop a note in the comments and I’ll find a good time for your city.

.....This will be early enough so that even young kids can see it, so drag everyone you can outside, and then come back here and we’ll compare notes on who was able to see it!

Alabama (Mobile)

.....Yikes! What are you doing inside? The only decent pass for you this week will be this evening (Sunday, November 8th). If you go outside and look to the southwest at 5:11:06 PM, the ISS will appear over the southwestern horizon. The Space Station will be just south of directly overhead, and it will vanish just above the northeastern horizon at 5:17:52.

http://www.heavens-above.com/PassDetails.asp?Session=kebgfgclbbkemgcihfjooook&satid=25544&date=40125.9680109606

Colorado (Denver)

.....Hey, I’m sorry, but you don’t have a great combination. Go here, see you get anything, and then wait for a better week.

http://www.heavens-above.com/PassSummary.aspx?satid=25544&Session=kebgfgclbakbpkhgkmjkhfod

Florida (Orlando)

.....Yikes! What are you doing inside? (Not a lot of good passes for the gulf states this week.) The only decent pass for you this week will be this evening (Sunday, November 8th), and the ISS will only appear about as bright as the brightest star, but it should be visible in evening twilight. If you go outside and look to the southwest at 6:09:53 PM (the same pass as Mobile is seeing), the ISS will appear over the southwestern horizon. The Space Station will reach an altitude of 33 degrees above the horizon, and will hug the western and then the northern horizon until it vanishes into the Earth’s shadow at 6:17:15 PM.

http://www.heavens-above.com/PassDetails.asp?Session=kebgfgclbbkemgcihfjooook&satid=25544&date=40125.9684758333

Georgia (Lookout Mountain)

.....See Tennessee (Chattanooga). You live in Chattanooga, get over it.

Massachusetts (Boston)

.....It won’t be great tomorrow, but from 6:33;37 to 6:40:04, the ISS will hug the western horizon going north, disappearing due north, and never getting more than 10 degrees above the horizon.

http://www.heavens-above.com/PassDetails.asp?Session=kebgfgclbakbpkhgkmjkhfod&satid=25544&date=40126.9844423032

Michigan (the southwestern UP)

..... There are a lot of great passes, a lot of crummy weather. Try tomorrow night from 5:34:41 to 5:40:04. The ISS will rise in the southwest, appearing to be aiming due east. The ISS will only get 26 degrees above the horizon, and will still be 23 degrees above the horizon when it disappears behind the Earth’s shadow.

http://www.heavens-above.com/PassSummary.aspx?satid=25544&Session=kebgfgclbakbpkhgkmjkhfod

Minnesota (Elbow Lake)

.....Okay, really, this a great week for seeing the ISS from the upper Midwest. Minnesota has a lot of passes, and the best days for Elbow Lake will be tomorrow (Monday), but the best pass will be Tuesday. There will be two tries on Monday, the first going from 5:34:12 to 5:39:28. It will rise in the south and skim the southern horizon, moving to due east, never getting more than 12 degrees above the horizon. Monday’s second pass will be from 7:10:04 to 7:11:27. The ISS will be about as bright as the star Sirius, and as you can guess from the time, it won’t be up very long. The ISS will rise in the southwest and disappear behind the Earth’s shadow when it is 25 degrees above the horizon.

.....Tuesday is supposed to be partly cloudy, and you will see another pass of the ISS disappearing on the way. Rising in the southwest, the ISS will pass very close by the planet Jupiter as it moves to the eastern horizon. The ISS will get 31 degrees above the horizon, and disappear into the Earth’s shadow when it is still 20 degrees up.

http://www.heavens-above.com/PassSummary.aspx?satid=25544&Session=kebgfgclbakbpkhgkmjkhfod

Minnesota (Twin Cities)

.....Tuesday is the best day for all of Minnesota this week. From 5:09:08 to 5:16:27, the ISS will be the brightest object in the sky as it moves from the southwest to the northeast, getting 65 degrees above the horizon.

http://www.heavens-above.com/PassDetails.asp?Session=kebgfgclbakbpkhgkmjkhfod&satid=25544&date=40125.9680122685

Minnesota (Winona)

.....The clearest day on the forecast is Tuesday, which is also the day this week of the best pass. On Tuesday, the ISS will rise in the darkening sky in the southwest, rising high overhead at 5:56:15, reaching 67 degrees above the horizon, until it disappears into the Earth’s shadow at 18:02:08, still 34 degrees above the eastern horizon.

http://www.heavens-above.com/PassDetails.asp?Session=kebgfgclbakbpkhgkmjkhfod&satid=25544&date=40128.0007469907

Pennsylvania (Harrisburg)

.....Harrisburg has an exceptional pass today, from 6:14:45 until 6:17:52. The ISS will rise in the southwest, and pass very high in the sky before disappearing into the Earth’s shadow while it is still 66 degrees above the horizon. If you don’t make this, then your next best shot is on Saturday when the ISS will never get above 17 degrees over the western to northern to eastern horizon from 5:19:29 to 5:26:46.

http://www.heavens-above.com/PassSummary.aspx?satid=25544&Session=kebgfgclbakbpkhgkmjkhfod

Pennsylvania (Philadelphia)

.....Philadelphia has an exceptional pass today, from 6:14:47 until 6:17:39. The ISS will rise in the southwest, and pass very high in the sky before disappearing into the Earth’s shadow while it is still 66 degrees above the horizon. If you don’t make this, then your next best shot is on Saturday when the ISS will never get above 17 degrees over the western to northern to eastern horizon from 5:21:56 to 5:25:29.

http://www.heavens-above.com/PassSummary.aspx?satid=25544&Session=kebgfgclbakbpkhgkmjkhfod

Tennessee (Chattanooga)

..... Chattanooga should have good weather on Wednesday and Thursday, so on Wednesday (just after sunset) look from 5:35:46 to 5:51:03 as the ISS, as bright as Jupiter, travels from south of west towards the north, to set in the northeast. The ISS will pass about halfway up the sky, at about 39 degrees above the horizon.

.....Thursday won’t be as bright, but from 6:06:54 to 6:15:36, the ISS will skin the northern horizon, west to east, getting only 15 degrees above the horizon.

http://www.heavens-above.com/PassSummary.aspx?satid=25544&Session=kebgfgclbakbpkhgkmjkhfod

Thursday, August 27, 2009

The Ghost of Mars

[It (rumor) has a hundred tongues, a hundred mouths, a voice of iron]

..........In mythology, Mars has many followers: Phobos and Deimos (fear and panic, and the namesakes for Mars' two "moons"), Eris (goddess of discord, now associated with a

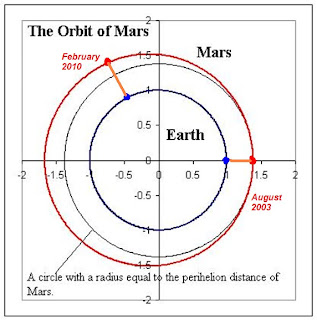

……… This email began in 2003, when there actually was a particularly close approach of Mars to the Earth. You may not remember Mars hanging in the sky like the full Moon; if so, don’t worry, you’re not crazy. Mars has a noticeably elliptical orbit, as I’ve shown in the first diagram. The Earth has an orbit that very close to circular. In the second diagram, the orbits of the Earth and Mars are drawn to scale in a way which emphasizes the oval nature of Mars’ orbit. Periodically (about once every twenty months or so), The Earth and Mars line up with the Sun, as the Earth passes Mars in its orbit. At this time, Mars appears larger than it otherwise would – but not by all that much.

……… This email began in 2003, when there actually was a particularly close approach of Mars to the Earth. You may not remember Mars hanging in the sky like the full Moon; if so, don’t worry, you’re not crazy. Mars has a noticeably elliptical orbit, as I’ve shown in the first diagram. The Earth has an orbit that very close to circular. In the second diagram, the orbits of the Earth and Mars are drawn to scale in a way which emphasizes the oval nature of Mars’ orbit. Periodically (about once every twenty months or so), The Earth and Mars line up with the Sun, as the Earth passes Mars in its orbit. At this time, Mars appears larger than it otherwise would – but not by all that much.

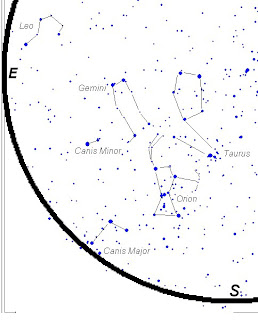

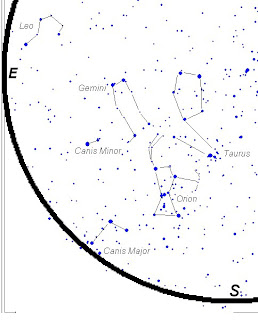

……….To begin with, the closest approach (which is referred to as “opposition”, because the Sun and Mars will be on opposite sides of the sky) in 2003 was indeed close … but as big as the full Moon? The full Moon certainly dominates the sky, and seems to be huge against the celestial sphere, but actually the Moon is only about half a degree across. This means that you could stretch about 360 moons from one horizon to the other. For a angle smaller than one degree, we break one degree into sixty “minutes of arc” (this is the Babylonians’ fault – they liked dividing by sixty instead of ten), so the Moon has a size of about thirty minutes of arc. How large will Mars appear? Mars at its largest will not even reach one minute of arc, so lets go one size down and divide minutes of arc into “seconds of arc”, so that the Moon is 1800 seconds of arc (written as 1800”) across. Mars at its largest had an apparent size of 25”. Now, that’s pretty big – for Mars. We’re rather far away from Mars right now, and it currently has an apparent size of 5.8”; if you are willing to get up before dawn and look for Mars, you can find it in the constellation Gemini, above the constellation of Orion. It will be strongly red and fairly bright, but still dimmer than the two brightest stars in Orion. The chart below shows the sky at about 5 AM. The next closest approach will be at the beginning of next February, and Mars will appear to be 14” across. The claim that “Mars will appear to be as big as the full Moon” came from a claim in one of the emails that “Mars would appear as large as the full Moon when seen through a telescope”. The qualifying phrase fell out of the email quickly, which is understandable in that it doesn’t make much sense. It seems strange to say “the Moon is 75 times larger than Mars” in a way that makes it seem that you should be able to wave at Martians.

……….So, in 2003, Mars did appear larger in telescopes than it normally does, and it did appear brighter in the sky. I confess that I had no compunction about using the close approach to get the word out at that time; when we had a Mars viewing at where I was working at the time (Texas A&M University – Kingsville) had more than seventy people show up, some of whom came under the mistaken impression that they would never be able to see Mars again. Now, we’re just back in the zone where Mars appears every two years or so, large enough to show a disk when seen through a telescope

……….A lot of the confusion has been caused by the fact that the emails that had been clear and precise about Mars back in 2003 didn’t reappear each year, where the confusing emails remain. Kinda makes sense, though, since the precise emails would have had “2003” on them, and people wouldn’t be sending them six years later.

………Before I go, I have another confession: I’ve never really enjoyed observing Mars. Mars is only visible about once every two years, it does not have moons visible in a small telescope, it does not have rings, even at its closest it appears smaller than Jupiter in the telescope. Furthermore, Mars has a thin atmosphere, thick enough for there to be dust storms that can cover the entire planet, and thin enough for the dust storms to last for weeks, turning the planet into nothing more than an orange dot in the telescope. Ah well, I’ll give it another try next year, and see how it goes …

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

How did your Perseids go?

..........The viewing event that we had for the Perseids drew thirty people, although not as many Perseids as in previous years. Too a lot of people's surprise, the next night also had a large number of Perseid meteors.

http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap090817.html

Thursday, August 6, 2009

The Perseid Meteor Shower

(please click on the image to go to the source for the above photo)

(please click on the image to go to the source for the above photo)

..........Allow me to now take a step backwards. One of the romantic draws of the night sky is the unchanging nature of the sky. If you could step into a time machine and step out on the same night of the year during the time of the first dynasty in Egypt, the sky would appear the same as it does tonight. (Well, someone who has observed for years might -- and I emphasize the "might" -- notice a slight difference in the position of a handful of stars, and the sky would be darker because there would be no city lights, near or far, vomiting out photons to make sure we don't miss a Burger King or a Wal-Mart, and the sky would be turning about a noticeably different point ... but I digress, and that belongs to my discussion of the Little Dipper.) As far as the stars are concerned, the sky would be the same. Certainly, if you have done something outside with your parents the sky will be the same when you do it with your children. Even with this, the most notable occurrences are those times that act against a temporary screen against the "permanence" of the unchanging heavens. Comets, shooting stars, and the predictable motions of the planets tend to draw our eyes first, something that defines the now against a backdrop with an unchanging, uncaring nature. These things are personal, even friendly.

..........Meteor showers are also excellent opportunities to get more into astronomy, or intrduce more people to astronomy. My parents were very supportive of my astronomy, but it can be hard to pull someone out into the cold night to look at a fuzzy bit in a telescope -- after I had been able to find it. The Perseids, especially, were times that other family members came out. I have a lot of memories of going outside as a group to watch the Perseids, even one time going to a state park in Alabama to watch the display.

.........The planets move according to a predictable pattern, bright comets come and go usually as they are discovered; most bright comets are -- individually -- a once in a lifetime object, at best. Meteors (shooting stars), however, come by at about a half-dozen or so a night. Even in suburbia, a patient observer in a lawn chair can expect to see a few each week.

..........Meteors, as a whole, can be divided into three parts. Some fraction of meteors are bits and pieces of rock that never got swept up by a planet, little bits of flotsam and jetsam that have been floating around for a few billion years since the beginning of the solar system. Some are pieces from our spacecraft. NASA traces the motions of thousands of objects that could represent a threat to spacecraft, and when your speed is measured in miles per second, a small nut, bolt, heat shield, etc., can be pretty scary. I lived in central Florida for four years, thirty minutes south of the Kennedy Space Center, and it took a good bit of the romance away from meteor watching realizing that a lot of the meteors I was seeing weren't primordial gypsies, but bits and pieces of junk, haunting the orbits where they had originally been sent. (Without specifically applied energy, a satellite will continue to pass over its launch point.)

..........The third class of meteor originates in comets. When people think of a comet, the bright fuzzy head and long tail are not constant parts of the comet, but creations of the Sun as the comet comes too close. The Sun's energy causes ice, the primary constituent of a comet, to burst from the surface. The bright appearance that people think of when you think "comet" is due to the cloud of reflective ice the Sun forces off of the surface. The tail is ice and gas raised from the comet trailing behind the nucleus. After the comet has begun retreating out to the farther reaches of the solar system, that stuff doesn't disappear, but stays in the same basic orbit. The first few times that the comet passes by the Sun, the ejected dust, dirt, and associated grit stays in the same basic place in the orbit; some meteor showers, like the Leonids in November (more about that then) have big peaks aligned with the period of the comet (in the case of the Leonids, this is every 33 years). The Perseid meteor shower is the result of the Comet Swift-Tuttle, and this is old enough to get a good shower every year. The shower is also young enough to get a good shower every year -- the comet hasn't already seen all its component bits and pieces burn up in our atmosphere.

..........According to most sources the Perseids produce about sixty meteors per hour, but this (like much else) presupposed that you are observing this shower from dark site out in the country. If you are, great! If you aren't, you will see less, but any sort of sky should give you at least twenty meteors an hour on the night of its peak. (There will be meteors for several nights before the peak from this shower, but the meteors will fall off strongly after the peak on the morning of August 12th.) These meteors are called Perseids because they appear to come from a point located in the constellation Perseus (reasonable enough). The reason why is that the stream of particles crosses the Earth's orbit in such a way, and at such an angle as to seem to come from a small area on the globe of the sky.

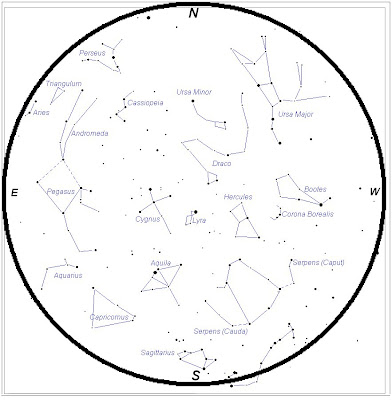

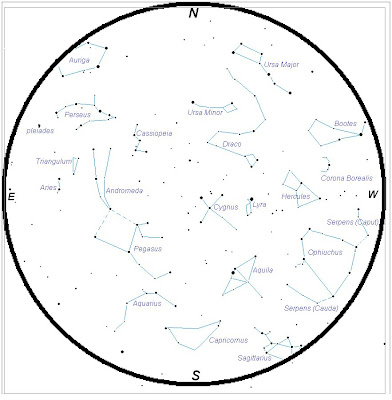

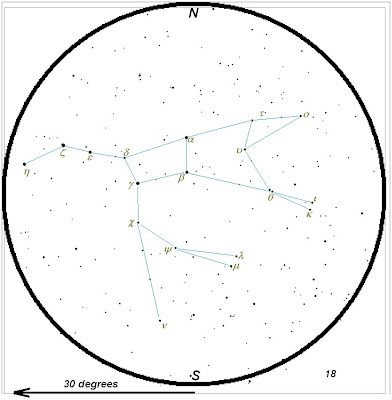

..........Below is a map of the sky as it appears soon after dark for the first part of August (for those in the latitudes of the upper United States; if you are observing from someplace like northern Europe or Florida, there will be a minor change of perspective, some constellations will be higher or lower to the north/south, but it will be eminently usable). This is an attempt to take the inverted bowl of the sky and squash it down into something that comes more easily out of the printer. To use it, turn the sheet (presumably printing it out first) until the point on the compass at the bottom of the sheet matches the direction in which you are facing. The stars just above the horizon will be the stars at the bottom of the sheet. The constellation of Perseus is just rising in the northeast.

..........Here is the night sky a little after midnight, in early August. At this time, the number of meteors should pick up a bit, and they will tend to be brighter than before, because the Earth's atmosphere will be hitting the meteors head-on.

..........Here is the night sky a little after midnight, in early August. At this time, the number of meteors should pick up a bit, and they will tend to be brighter than before, because the Earth's atmosphere will be hitting the meteors head-on. ......... Something that I have none done successfully (so far) is to keep a diary, so to speak, of the Perseids. Using a red flashlight (to avoid ruining your ability to see at night), take a print-out of the sky and sketch the paths of meteors after you see them. If you hope to be out for some time, take several: use one for 10 PM to 10:30, one for 10:30 PM to 11, and so on. One sheet for an extended period of time for the Perseids might look like the one below. This also illustrates why they are named the "Perseids"; if you keep track of the meteors that you see on the night of the eleventh, most of them should appear to radiate out from a point in the constellation Perseus (the "radiant" of the meteor shower, naturally enough).

......... Something that I have none done successfully (so far) is to keep a diary, so to speak, of the Perseids. Using a red flashlight (to avoid ruining your ability to see at night), take a print-out of the sky and sketch the paths of meteors after you see them. If you hope to be out for some time, take several: use one for 10 PM to 10:30, one for 10:30 PM to 11, and so on. One sheet for an extended period of time for the Perseids might look like the one below. This also illustrates why they are named the "Perseids"; if you keep track of the meteors that you see on the night of the eleventh, most of them should appear to radiate out from a point in the constellation Perseus (the "radiant" of the meteor shower, naturally enough).Tuesday, July 21, 2009

Forty Years +1

.........Yesterday was the fortieth anniversary of the Moon landing, the first of the only six times in history that humans have actually walked on

another planetary body. I was a little less than two when this happened, and by the time my youngest brother was born we had left the Moon, and we haven't been back since.

another planetary body. I was a little less than two when this happened, and by the time my youngest brother was born we had left the Moon, and we haven't been back since..........There have been a number of responses that I have seen to this fact. One of the drives for reaching the Moon was to "win" the space race against the Soviet Union. Once this was done, this part of the impulse was gone. We had already run this race, why stand around at the finish line instead of going out for pizza and beer? (That would be "root beer" if you're under twenty-one.)

..........Ratings for even the second Moon landing were well below that of the first, and it seemed as if there was no enthusiasm among the general population for more Moon shots. The Lunar program was also seen as a Democratic program (the landing was just six months after Nixon's inauguration), and it might have suffered from this view under Nixon and Ford. After Apollo 17, the space program turned to the shuttle, seen as preparation for a next step, but which seemed to become its own destination. Even the space station has been its own end. What next? Are we as far as we can go? Are we as far as have the will to go?

..........Another question that is asked concerns our use of resources, and this is certainly not an idle or non-compelling question, especially now. What could we do with the money that space exploration or NASA in general uses with people in poverty, desperate need of health care, and the job market dropping like the morale of a football team once Terrell Owens signs up?

..........Also, we must consider the question of priorities, even if we can assume that amount of money going into space science. Is it good to fund manned missions, or should we use the same money to fund a number of smaller efforts, in which a greater number of people can take part?

..........All of these questions demand a good answer, and I will even go so far as to say that in order to support more manned missions, an argument must be made that justifies a program against all of these points. Can a space program do more than just beat "the enemy" somewhere, and produce more in the public imagination beyond Tang (TM)? To make this argument, I want to make a wider claim about what the Moon landing provided.

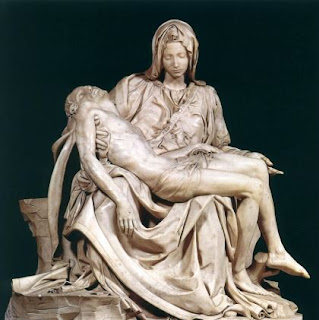

..........Consider the object shown to the left. What is the value of this? Is this simply a waste of good marble that could have been ground up and used as the basis for houses, sewers, roads, etc? Is the value of this equal to the value of the material that makes it up, or the use to which the material could be put? I will venture to say that most people would say "no" to the last few questions, to acknowledge that art as a human creation has a value in the act of cultural, human expression. That beyond the day to day needs of basic human existence, we have a need that is higher, to make a higher purpose, a reason why we are here, a calling to others to acknowledge something even higher to which human beings can aspire. Even art taken as entirely secular still speaks to the fundamental human desire to define meaning for ourselves, to create ourselves as some thing above day-to-day existence. The Moon landing also made the argument that human beings can create a meaning for themselves in an even wider fashion. The statue I picked was the work of one man's genius, but the Moon landing required scientists to plot the way there, engineers to create the materials we needed to get there and back, and what we needed to keep people alive on the trip, people brave enough to risk everything on the say-so of people who had never done this before and the skills to handle what could come up, and taxpayers.

..........Consider the object shown to the left. What is the value of this? Is this simply a waste of good marble that could have been ground up and used as the basis for houses, sewers, roads, etc? Is the value of this equal to the value of the material that makes it up, or the use to which the material could be put? I will venture to say that most people would say "no" to the last few questions, to acknowledge that art as a human creation has a value in the act of cultural, human expression. That beyond the day to day needs of basic human existence, we have a need that is higher, to make a higher purpose, a reason why we are here, a calling to others to acknowledge something even higher to which human beings can aspire. Even art taken as entirely secular still speaks to the fundamental human desire to define meaning for ourselves, to create ourselves as some thing above day-to-day existence. The Moon landing also made the argument that human beings can create a meaning for themselves in an even wider fashion. The statue I picked was the work of one man's genius, but the Moon landing required scientists to plot the way there, engineers to create the materials we needed to get there and back, and what we needed to keep people alive on the trip, people brave enough to risk everything on the say-so of people who had never done this before and the skills to handle what could come up, and taxpayers. ..........Lots of taxpayers. On the other hand, this enabled everyone in the country to take pride in and ownership of the Moon landing, and justifiably so, in my opinion. This, I would say, is something that we need again now.

..........When John F. Kennedy called for human exploration of the Moon, the United States was in an excellent position to commit ourselves to a great leap, a tremendous effort that we could do because the US was at the zenith of its power. The recovery of the rest of the world, directly affected in World War II, was still at the point where they were a tremendous market for the rest of the world, and had not yet returned to the production capacity that the rest of the world had before. Today is drastically different, but a space program with a clear human goal of a sustained presence on the Moon or a trip to Mars could restore not military leadership, not technological (though it would help) leadership, but leadership of vision. I can most honestly speak of this in terms of what the space program meant to me.

..........What did the landing on the Moon mean to me? I didn't gain an interest in astronomy when I was one and a half, but over the next few years I do remember watching the astronauts returning to Earth, and being recovered by aircraft carriers (yes, Keith, I know those were SEALs), and I can remember my amazement at considering that people, actual people, were capable of firing a rocket (essentially a big, controlled bomb) off from the Earth, using it to send people into space, and then being able to work out where they would come back with such accuracy that there could be ships waiting right there to pick them up. As the seventies aged, I saw a rush of people for magic, whether it was transcendental meditation, astrology, weird new medical fads in which people hoped for some way of cheating of the universe, some way of the controlling it to get the result they wanted. I was not brought up to be "afraid" of math, as if math was some magical field that only special people could do, so even at seven I was confused about why people would turn away from the examples of all the best that we could do to trust in something with no results, but which felt nicer, as if you could ask the universe for something, and how much you believed, or how nice you were actually counted. People have even sidestepped what human beings can do to hope to jump past them, to imagine aliens visiting the Earth who will solve all of our problems if we just ask them nicely enough.

..........There is no evidence of that ever happening, and no evidence of any magic, or any space cavalry to come riding over the hill and save us from the problems that we made for ourselves. All we have is us. We have problems that we cannot solve simply by saying, "I'm fine; let each person solve this independently." We have problems that cannot be solved state by state, and now even nation by nation. As we need to work together (not *under* each other, but as a collection of individuals/localities/states/nations) we should have something that will give us an experience of true greatness, something that needs all of us to work together, and shows us that we can do what seems impossible, to give the renewal of will and the hope that our more tractable problems like disease, poverty, hunger, etc., ad infinitum, are within our reach themselves.

Friday, July 17, 2009

Ursa Major (part 3 of 3)

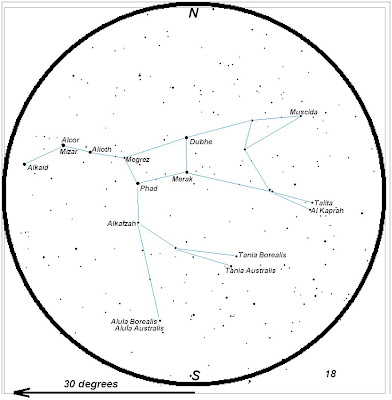

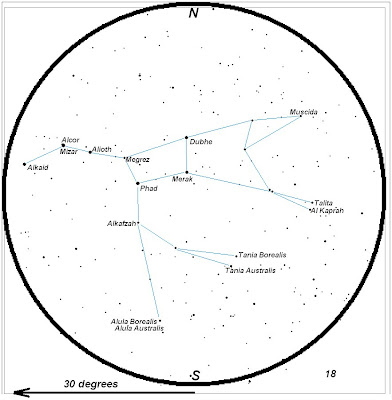

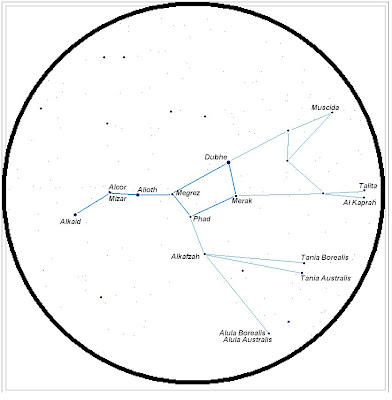

.........Wednesday night I was fortunate enough to have a wonderfully clear night, so I was able to double-check all of my impressions of the appearances, the methods of finding Messier Objects, and the maps that I have made for this purpose. Each of the Messier objects will appear with a star map showing you how to get from a bright (well, fairly bright ... well, identifiable) star to the object. Each map will be on a different scale -- some objects are close to bright stars, and some require more of a trip. On each map will be indicators matched to the field of view of common telescopes. If you can fit the entire full moon in the field of view of your telescope, then you can use my circles as good guides as to the sizes of the steps that you are going to have to make to get where you need to go.

..........Because of the name of the blog, my first pass through the sky (the first year of the blog) will cover the Messier objects, constellation by constellation. (For most constellations, I’ll be able to do this in the same entry; the Big Dipper is unusual.) There are seven (eight) Messier objects in the area of the Big Dipper, and I’ll cover them in numerical order. This is a bit unfortunate, because the first Messier object on the list, the first Messier object I’ll cover here, is …

M 40: The Lamest Messier Object of Them All …

Difficulty Level: 2 (Close to a bright star, only one jump.)

.........Because M40 is the lowest-numbered Messier object in the first constellation I’m talking about then this is the first one I’m covering, which is a bit unfortunate, all things considered. Responding to the report of Johann Hevelius, who claimed to see a nebulous patch in this area, Charles Messier attempted to find the object at the location the other astronomer gave, only to discover nothing at all. It’s quite possible that the original observer actually did see a comet but didn’t recognize it as such, and recorded it essentially as "gunk that gets in the way of identifying comets".

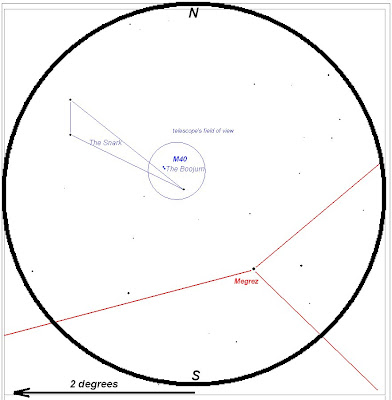

..........For some reason, Messier felt the need to identify something in the area with Hevelius’s observation, so a double star was identified as “M40”. (As it turns out, this even isn’t a double star, but simply two stars along the same line of sight.) If you would like to find this “object”, the path is easy enough. Start with d Ursa Majoris (Megrez), the star connecting the handle to the bowl. Just above Megrez is a triangle of stars that should all appear easily enough in your finder scope or binoculars, which leads me into a bit of an aside, since this is the first example of star-hopping that I'm using.

........When mapping a way from a bright star to a fainter object of interest, I’ll use patterns of stars (asterisms) to help fix the image in memory, but in this case I was a bit put off because it is a little hard to make anything besides a triangle from three nonlinear stars, but inspiration has struck, and I will name this asterism “the Snark”! (I'll explain this in just a second.)

.........To find M40, which I will therefore name “Boojum”, find the lowest star in the triangle (the one closest to Megrez) in the eyepiece, and the optical double which has inherited the name M40 will enter your field from the north if the star (which has the name 70 Ursae Majoris, unless you have a better name for it) is moved to the southern edge of your field. The Boojum is one of the easiest Messier Objects to find, and (sadly) one of the least interesting. Okay, it is the least interesting Messier Object.

.........Why does the substitute for a disappearing Messier object get named “the Boojum”? I took this from Lewis Carroll’s poem, “The Hunting of the Snark”.

.........To help you get an idea of the brightnesses of starts seen through the telescope, the two stars that are The Boojum are ninth magnitude (9.0), about the limit of stars in the smallest telescopes. It will be good to use this to get an idea of how easy it will be to find other Messier objects, ones that are a lot more interesting.

M 81 and M 82: "I'm not touching you, am I bugging you?" Galaxies

Difficulty Class: 3 (Some jumps through asterisms)

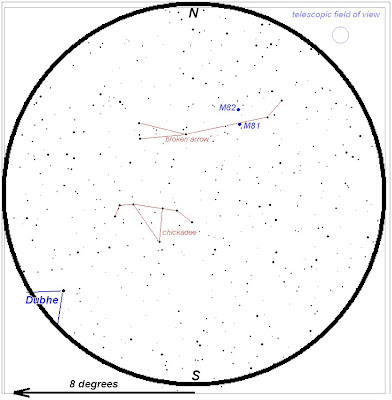

.........To my mind, the jewels of the Big Dipper are the two nearby galaxies (near to each other, and relatively close to the Milky Way) M 81 and M82. From my point of view, these are some of the easiest galaxies to find, although you may find differently. These were some of the first deep-sky objects that I learned to find, so the asterisms that I use to find them might not appear to be as obvious to you.

Start at the end of the Dipper bowl (the star Dubhe), look north of Dubhe, and a bit to the west. In less of a shift than it would take to go from Dubhe to Merak, you will find some stars that appear to me to be a mirror-reversed Greek letter tau. Since I’m printing this on a map instead of just trying to remember a path at the telescope, I am naming this the asterism "The Chickadee". Once you’ve found this, center the Chickadee in the center of your binoculars/finder scope. If you now go due north, you’ll find what I call the broken arrow (this one needs a better name – any ideas?) : a triangle of stars that appears to me to be the back end of the arrow, which can be traced east to a star with another star of about the same brightness off the line, giving to me the appearance of a broken arrow. Visible in binoculars or a telescope’s finder scope as two faint fuzzy patches about two-thirds of the way closer to the break in the arrow than the fletching are the two galaxies we are looking for. (If you can’t see the galaxies in a finder scope, just aim for a point along the line of the arrow and hope for the best. (As always, if you don’t see the galaxies in the telescope then unlock the telescope and search in increasing circles from your starting point. Never underestimate the importance of patience in astronomy.)

..........M81 and M82 are reasonably close (as galaxies go) at a mere twelve million light years away. These galaxies appear close together in the sky because, in this case, they actual are close to each other – and they used to be closer, which affected in ways even visible now.

M81: Bode’s Galaxy

.........M81 was first discovered by Johann Elert Bode in 1774, and is often called "Bode's Galaxy". The total brightness of this galaxy is magnitude 6.9, implying that the object should be fairly bright, but this can be misleading. By luck, I started this so that the final constellations that I talk about will be constellations with a lot of galaxies. This is lucky because galaxies can be some of the hardest objects to observe. In stars, including clusters of stars, we’re looking at a lot of point sources of light – even with streetlights, moonlight, etc., clusters can still be seen. In galaxies and nebulae, the light is smeared over an area; any increase in the background light can drown out the image entirely.

..........Bode’s Galaxy is a fairly reliable target, a face-on spiral galaxy will two bright arms. It will appear as a bright smeared dot of light, and on the very clearest and darkest of nights, the two spiral arms of M81 will be visible as well.

.........I have an anecdote about Bode's Galaxy that I now feel compelled to share (otherwise, you ould just skip to the next paragraph.) In 1993, a supernova was observed in M81 and, as these things do, for a few weeks that one dying star gave out as much light as the rest of that galaxy. This made a lot of news, as there is lot of physics and astronomy that we can learn from supernovae, plus it was cool to watch. At that time, I was living close to Cape Canaveral, and had the opportunity to watch a night launch of the space shuttle. I had brought my telescope to the launch site to get a close view of the shuttle, but after a while of counting heat tiles, I began to get distracted. On a whim, and not expecting very much because we were surrounded on all sides by brilliant streetlights, I aimed the telescope at Dubhe, and moved the scope about as far as I remembered it being to the west, and then north, to get to M81, and looked in the telescope. By some astounding quirk of luck (although I tried to pretend that it was skill), I could see the field with M81 in the telescope! The galaxy was invisible due to all of the background light, but the star field plus the supernova was recognizable. There, my secret is now out.

M82: The Starburst Galaxy / Cigar Galaxy

.........With M81 in the center of the field of view, one can move the telescope so that M81 moves to out of the southern edge of the field of view, and then move the telescope gently along the other axis, and M82 will appear, a thin jagged line of light. The Starburst Galaxy is an irregular galaxy that can almost fit in the same field of view with M81. Galaxies are divided into four major groups: spiral galaxies, barred spiral galaxies (a spiral galaxy with a bar structure in the core), elliptical galaxies, and “irregular” galaxies, galaxies in which something has happened to distort the shape of the galaxy. In the case of M82, this was a close pass, in which M81 caused a lot of the gas clouds in M82 to collapse into new stars. More recent studies show that M82 is probably a barred spiral galaxy seen edge on, with the burst of new star formation somewhat hiding the shape.

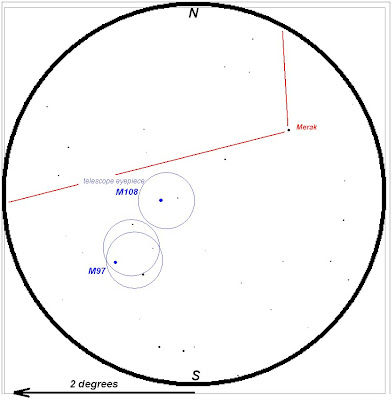

M 97: The Owl Nebula m = 11.20

Difficulty Level: 5 (close to a bright star, but individually quite faint.)

.........I’ve found the Owl Nebula one of the hardest Messier objects to find in the sky. At a total visual magnitude of 11.20, and that is considering all of the light concentrated at one point, which it most certainly does not. I wouldn’t advise looking for the Owl Nebula on anything but clear, moonless nights.

.........The Owl Nebula is a planetary nebula, made up of a rough bubble of gas ejected from a star as it goes into "retirement", casting off its outer layers and becoming a white dwarf. A planetary nebula is an expanding cloud of gas, so it has a limited lifespan, until the cloud gets to diffuse to see, or too far from the central remant of the star to shine in absorbed and reemitted light. this puts a clock on it of about one hundred thousand years. A long time as far as library fines go, but nothing on the time scale of stellar existences. There are therefore relatively few planetary nebulae (only four in Messier's list), and this is the hardest to see.

M101: Didymus

m = 7.70

Difficulty Level: 4 (Easy star hop, individually faint)

.........This galaxy is a large, face-on spiral, quite an impressive sight that will even allow you to see the spiral arms, but the night has to be pretty much perfect. On my excellent viewing night this week, I was able to star-hop to the correct field, and see all of the stars that I was supposed to see, but there was no sign of the galaxy. Stuff like this gave rise to my third law of living, "You can do nothing wrong, and still lose."

.........Messier 101 was named "Didymus" (by me) because it is its own twin, of a sort. Charles Messier recorded this galaxy as M101 and later recorded the same galaxy as M102. In the case of M40, Messier found something nearby and get it a number. In the case of the galaxy M91, in Virgo, Messier recorded a non-comet at a position where nothing was later found, and the number was simply assigned to another galaxy nearby that was bright enough to have been seen by Messier, but was otherwise unrecorded.

M108: Galaxy

M108: Galaxy

m = 10.10

.......... Both M108 and M109 are faint spiral galaxies that are difficult to observe when the night is not completely dark, and the sky is not completely clear. M108 can be found on the same star map as M97.

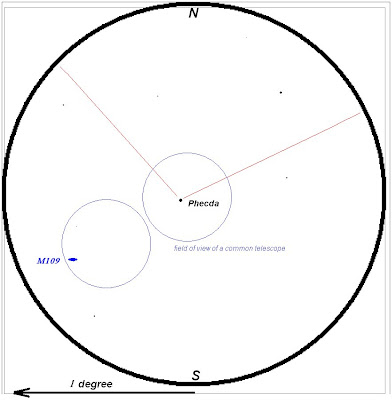

M109: Galaxy

m = 9.80

..........Both M108 and M109 are faint spiral galaxies that are difficult to observe when the night is not completely dark, and the sky is not completely clear.

Difficulty Level: 4 (Easy star hop, individually faint)

Sunday, July 5, 2009

Ursa Major, Part 2 of 3 (Blog #4)

As the Antipodes are unto us,

Or as South to the Septentrion”

Wednesday, July 1, 2009

Ursa Major, Part 1 of 3 (Blog #3)

..........This entry is much later than I had hoped it would be, and it has grown into quite a monster in the meantime – I promise, this is larger than the standard entry will be, and much more space than the average constellation will get. Heck, I had to break Ursa Major in three parts! This is part I, "Ursa Major As a Guide to the Sky". The next two will be "Ursa Major, the Constellation" and "Ursa Major, Telescope Stuff". Posting frequency will drop to (probably) once per week in the fall, but I want to post more frequently in the summer. For example, I hope to finish Ursa Major this week.

Downloading

.........Much of the writing time between posting was directed to working out a way to make star maps that were done entirely by myself, so that I could replicate them as I would. However, once I post these as images, much of the detail gets lost; to correct this, I have uploaded the image files to a Google discussion group. (If you choose, you are free to ask questions about the blog, certain topics, or things that you would like to see there, but I would appreciate if you would comment about individual blogs in the space after the blog entry.) There, you may download the images to get maps that I hope you might find useful.

My Starting Point

.........There is

Naming Stars

.........The Big Dipper can also serve to introduce how stars are tracked individually as well. Of all the stars that can be seen with the naked eye (there are slightly more than 5,000 as the HIPPARCOS satellites saw it), there are about two hundred that have individual names. These are typically the brightest stars in a constellation, and show the limits of the usefulness of designating stars individually in such a unique manner; after all, could you reliably remember five thousand names? (Heck, have you ever had to correct a grandparent or other family member? Odds are, there aren’t five thousand in the family.) Here is a star map of Ursa Major with all of the named stars shown: (at least, before people start claiming stars to name themselves.)

.........Another method was derived by Johann Hevelius in a star atlas published in 1603. He tried to name the brightest star in a constellation “alpha of that constellation”, so the brightest star in Ursa Major should be a Ursae Majoris (then b, g, d, and so on). Ursa Major is an unfortunate starting point for introducing this system, because in this case, as you can see, Hevelius simply started by making a pattern of the Big Dipper. Here is a map of the Big Dipper with stars named in this system:

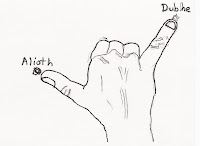

.........The stars of the Big Dipper can also be used to provide a sense of scale across the sky. Judging scale is one of the biggest problems in getting used to moving around the sky, because in the sky there are no points of reference that we see on the ground. Fortunately, we have fairly reliable measurement tools at the end of our arms – we can use our hands. (Yes, your hands are almost certainly not the same size as mine, but your arms are also differently sized than mine as well. This balances out.)

.........The stars of the Big Dipper can also be used to provide a sense of scale across the sky. Judging scale is one of the biggest problems in getting used to moving around the sky, because in the sky there are no points of reference that we see on the ground. Fortunately, we have fairly reliable measurement tools at the end of our arms – we can use our hands. (Yes, your hands are almost certainly not the same size as mine, but your arms are also differently sized than mine as well. This balances out.) .........Consider the “distance” between the stars Dubhe and Merak. I put the word “distance” in  quotes, because we have to define what we mean by distance. If I describe the physical distance as 45 light years, how does that help you? We’ll use “distance” to refer to the angular distance between two things in the sky, so that an object on the horizon due north will be 180⁰ away from an object just above the horizon due south. In this way, the distance between these two stars is just a little bit more than five degrees. As shown in the diagram below, this distance against the sky is about the same as the angular size of three fingers held at arm’s length. This can also be used as an order to your bartender if the viewing isn’t good. (PARENTS: If you little one comes in, sighs, and says, “Gimme three fingers of Redpop”, then s/he has been reading this blog.)

quotes, because we have to define what we mean by distance. If I describe the physical distance as 45 light years, how does that help you? We’ll use “distance” to refer to the angular distance between two things in the sky, so that an object on the horizon due north will be 180⁰ away from an object just above the horizon due south. In this way, the distance between these two stars is just a little bit more than five degrees. As shown in the diagram below, this distance against the sky is about the same as the angular size of three fingers held at arm’s length. This can also be used as an order to your bartender if the viewing isn’t good. (PARENTS: If you little one comes in, sighs, and says, “Gimme three fingers of Redpop”, then s/he has been reading this blog.)

.........The stars Dubhe and Phad are ten degrees apart. This is about the distance between your fingertips is you extend your hand as shown below, a form that is either reminiscent of a certain arachnid-based superhero from a company with “marvelous” lawyers, or – if you were a young person in the 70’s or 80’s – the “secret devil sign” beloved by metal bands and freaked out middle-aged PTA moms. Of course, if a freaked-out PTA grandma sees you making a devil sign to the night sky, then you might need to refer back to the “three fingers” – once the police leave.

.........The stars Dubhe and Phad are ten degrees apart. This is about the distance between your fingertips is you extend your hand as shown below, a form that is either reminiscent of a certain arachnid-based superhero from a company with “marvelous” lawyers, or – if you were a young person in the 70’s or 80’s – the “secret devil sign” beloved by metal bands and freaked out middle-aged PTA moms. Of course, if a freaked-out PTA grandma sees you making a devil sign to the night sky, then you might need to refer back to the “three fingers” – once the police leave.

.........The stars Dubhe and Alioth are fifteen degrees apart, which can be measured by the hand sign below, which I have christened the “dude”. (Pronounced “duuuuuuuuude”.)

.........The Big Dipper can also be used as a guide around the sky as well. A line that passes through Merak and Dubhe will pass very close to the North Celestial Pole, and hence, the North Star. (This is helpful, because while the North Star Polaris is a reasonably bright star, it is nowhere near the brightest star in the sky, though this is a common misconception.)

........Get familiar with the Dipper and the stars around it, and I'll be back to write about the stars of the Dipper itself, and a famous test of vision across the ancient world.

........Get familiar with the Dipper and the stars around it, and I'll be back to write about the stars of the Dipper itself, and a famous test of vision across the ancient world.Saturday, June 20, 2009

A Constellation Preview (Blog #2)

Now if I can only find a way to make the image display with the detail that I want it to show ...

Thursday, June 18, 2009

The Planets Right Now (Actually Saturn, Saturn, and More Saturn) (Blog #1)

PREFACE: I’m going to rely more strongly on sketches I make at the telescope than on photographs, because photos can be a lot cooler than what you can see with eye – the photo can be taken over a long period of time, and reveal colors and structures that we can’t see by eye. This is actually one of the complaints that I have about a number of observing aides; by showing photos with more details than the eye can see, a visual observer could be greatly discouraged instead of being able to learn to see what is there. Happily, planets do not have that problem. Planets are so comparatively bright that sensitivity is not a problem, and in fact the eye does a better job than most non-spacecraft cameras for seeing details on the planets. Plus, there are some really cool planetary images in the public domain.

The primary purpose of my blog over the first year will be discuss each constellation visible from the continental United States in turn, with special emphasis to the Messier Catalog, Charles Messier’s list of 110 galaxies, clusters, nebulae, and … stuff. (I’ll explain that in my first constellation post on Ursa Major – the Big Dipper and more). I’m not just going to be doing that, because I want this to be interesting for anyone who might just be starting a relationship in the night sky.

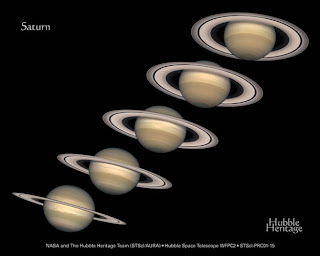

Some of the easiest objects to find and watch in the sky are the planets, and there is a good reason to have a post about where the planets are right now (and what they are doing), and that brings us to the first planet we will look at, Saturn. Saturn is the sixth planet out from the Sun, and the second largest planet, but the aspect of Saturn that everybody rightfully thinks of is its ring system.

The rings of Saturn are so bright because they are largely made of ice particles, and the diameter

of the ring system is over one hundred and twenty thousand miles across – but the rings are only a few miles thick. We can see the rings of Saturn because Saturn’s orbit is tilted slightly compared to the Earth’s, but even with a tilt, there are still two times during Saturn’s orbit around the Sun at which Saturn is in the same plane as the Earth and we look at Saturn’s rings edge on. At these times, the rings seem to vanish altogether! The next time this happens will be in late September, but Saturn will be too close to the Sun to see, so go ahead and look now, if you have even a small telescope, to see Saturn’s rings as a narrow line.

of the ring system is over one hundred and twenty thousand miles across – but the rings are only a few miles thick. We can see the rings of Saturn because Saturn’s orbit is tilted slightly compared to the Earth’s, but even with a tilt, there are still two times during Saturn’s orbit around the Sun at which Saturn is in the same plane as the Earth and we look at Saturn’s rings edge on. At these times, the rings seem to vanish altogether! The next time this happens will be in late September, but Saturn will be too close to the Sun to see, so go ahead and look now, if you have even a small telescope, to see Saturn’s rings as a narrow line.(The disappearing rings were noted by the first person to look at Saturn through a telescope, Galileo, who only saw indistinct shapes on Saturn’s sides. In Greek mythology, the titan Cronos – associated with the Roman ‘Saturn’, although that isn’t really … but I digress – who swallowed his children as they were born to thwart a prediction that his child would supplant him. When Galileo saw “Saturn swallowing his children”, he was so frustrated that he stopped observing Saturn at all.)

Saturn can be found in the west as night falls, south the constellation of Leo. If you are looking above the western horizon, the map below shows you approximately what you would see, without the names and big blue lines. If you have any city lights in the vicinity, then you might just see the stars whose names I have included.

If you want to be sure if you are recognizing the stars correctly, I have included a map from my first constellation blog showing some of the stars that can be found from the Big Dipper. If you can find the Big Dipper high in the sky, then you can follow the two stars of the bowl that connects to the handle along a line that comes very close to the star Regulus.

That’s all we have in the evening, but if you are actually getting up early some morning to look for the space station, or if you just have a time when you can’t sleep, the planet Jupiter (the fifth planet, and the largest planet in the solar system) will be high in the southern sky, and Jupiter will be by far the brightest thing in the area. If you were to look at Jupiter in even a small telescope, the four largest moons of Jupiter (on the same size scale as our own Moon) will appear as a line of stars. The planet Neptune (the eighth planet, about four times the radius of the Earth) is actually very close to Jupiter in the sky right now. If you are able to find Jupiter in a telescope, and you can tear yourself away from the view of the moons, and the bright bands and dark zones of Jupiter’s cloudtops, then you can try and find the planet Neptune to the north and east of Jupiter. Neptune is fainter even than the moons of Jupiter, and shows you as little. While telescopes will show the disk of the planet Neptune, and you can see the strong blue color caused by the methane clouds of Neptune’s atmosphere, that’s all that you get. No matter how strongly you magnify that image, neither Neptune nor Uranus (a little harder to find) will show any features whatsoever. Mark off that you have seen Neptune (hurrah!) and go back to Jupiter.

That’s all we have in the evening, but if you are actually getting up early some morning to look for the space station, or if you just have a time when you can’t sleep, the planet Jupiter (the fifth planet, and the largest planet in the solar system) will be high in the southern sky, and Jupiter will be by far the brightest thing in the area. If you were to look at Jupiter in even a small telescope, the four largest moons of Jupiter (on the same size scale as our own Moon) will appear as a line of stars. The planet Neptune (the eighth planet, about four times the radius of the Earth) is actually very close to Jupiter in the sky right now. If you are able to find Jupiter in a telescope, and you can tear yourself away from the view of the moons, and the bright bands and dark zones of Jupiter’s cloudtops, then you can try and find the planet Neptune to the north and east of Jupiter. Neptune is fainter even than the moons of Jupiter, and shows you as little. While telescopes will show the disk of the planet Neptune, and you can see the strong blue color caused by the methane clouds of Neptune’s atmosphere, that’s all that you get. No matter how strongly you magnify that image, neither Neptune nor Uranus (a little harder to find) will show any features whatsoever. Mark off that you have seen Neptune (hurrah!) and go back to Jupiter.Uranus is much harder to find, located in the constellation of Pisces, which has no bright stars to speak of. I’ll go into more depth in finding Uranus when it becomes more of a evening star.

Venus and Mars are both morning stars right now, visible in the east before sunrise. Venus will be high enough in the sky to find easily. From Venus, Mars is close to the north, and both should be visible in the same field in binoculars. Mercury, the last planet to rise tonight, will rise shortly before the Sun, and would be very, very difficult to find.

(I’m waiting to get into the whole Pluto thing til its own entry. Pluto is up tonight, but forget about seeing it. My own telescope is too small to see Pluto, and even if I could, it would only appear as a dot. Really, this blog is about Saturn.)

Glossary (Blog #0)

ASTERISM:

An asterism is a pattern of stars that is not a CONSTELLATION (which see). I’ll make up patterns of stars to help find some objects off the beaten path, and I’ll introduce some identified asterism as we go.

BRIGHTNESS:

Brightness describes how an object appears from Earth, and so doesn’t actually say anything about the object itself. There are stars that are bright because they are close to us, and stars that put out much more light, but are dimmer because they are farther away.

Brightness is measured in magnitudes, in an idea going back to the Greek astronomer Hipparchus. Hipparchus labeled the brightest visible stars as “stars of the first rank”, and the dimmest stars as “stars of the sixth rank”. Tradition is a powerful force, and this has remained the pattern even as we now have technology able to measure just how much light is coming off of a star. The faintest stars that can be seen with the naked eye (see “named stars”) are sixth magnitude, and first magnitude stars are some of the brightest stars in the sky. The magnitude system is not linear because the eye’s response is not linear. The system is defined such that a star with a magnitude of m = 1.00 provides 100 times as much light as a star with m = 6.00. This means that brightnesses can be unintuitive to the point of frustration. The brightest star, Sirius, has a magnitude of -1.4, the planet Venus can get as bright as -4, and the Sun has a visual magnitude of -26.

CONSTELLATION

A constellation is an arrangement of stars that has long been considered to represent some figure or object. Most cultures had their own set of constellations (some cultures named individual stars, some probably had their own but got culturally co-opted by some other group), but the “official” set was settled upon by the International Astronomical Union (the same people who disqualified Pluto) in 1930 based upon the Roman constellations taken from the Greeks, some of which they took from the Babylonians, Indians, and more. There are 88 accepted constellations.

DOUBLE STAR

A double star is a system in which two stars are actually orbiting around a common center of mass. There are many sets of double stars that are close enough to Earth to make interesting things to see, there are some that are interesting because the orbits of the two stars actually cause them to eclipse each other as seen from Earth, and there are also some stars (called “optical doubles” that have been identified as double stars, but were later discovered to have simply been in the same line of sight, and nowhere near each other.

NAMED STARS

There are about six thousand stars visible to the naked eye in the sky. (I wonder if this is going to mean I get some hits if someone googles “naked”? Hmmm … naked naked naked naked …) Less than two hundred stars have individual names, primarily because remembering six thousand names is a little problematic. Still, the brightest stars all largely have names, and the commonly accepted names are largely from the Arabic. (I am not sure why Greeks named constellations and Arabs named stars. Perhaps Greek navigators didn’t need to be as precise navigating in the Mediterranean as Arabic travelers needed to be in the Indian Sea and aiming for small oases in big deserts.)

When I post star maps, I’ll post the names of all identified stars. If I miss any, I’ll try and fix that. This brings up an interesting point. For some years, there have been companies that allow you to “name” a star for a person. This is official – as far as that company is concerned, but nobody else knows about it. Have something cheaper! If you want to name a star, pick a star that has no name associated with it and send it to me (one per person, please), and I’ll mark it one the Messier Pro maps.

TIME:

When I refer to how the sky will appear on a certain night, unless I specifically refer to a certain time, I will be speaking of a time an hour after twilight has ended. This will generally be about two hours after sunset, and it will change over the course of the year. This “observing time” will be marked on the post, although any descriptions I give will be good for some time before and after “observing time” (unless I refer to something close to the western horizon).